Letter from MHQ: How Ink Went to War

Richard Fleischer, the director of the American sequences of Tora! Tora! Tora!, the 1970 film that is the subject of Wendell Jamieson’s cover story in this issue of MHQ, was a gifted Hollywood veteran whose other credits included The Narrow Margin (1952), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), The Vikings (1958), Compulsion (1959), and Dr. Doolittle (1967). “One could say that he’d been in the movies since he was born,” Jamieson writes of Fleischer, noting that his father, Max, was one of the industry’s earliest and most creative animators, directors, and producers.

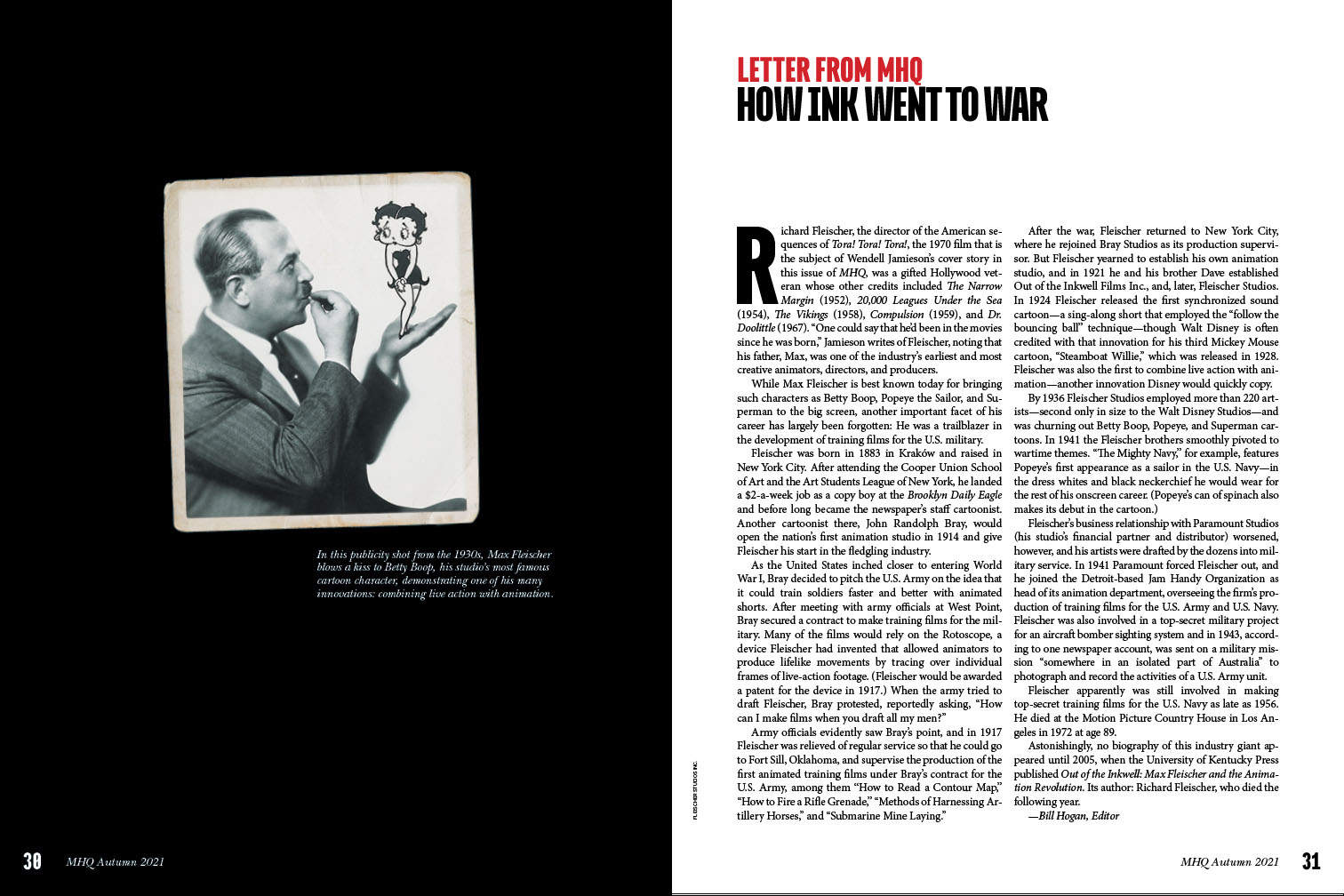

While Max Fleischer is best known today for bringing such characters as Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor, and Superman to the big screen, another important facet of his career has largely been forgotten: He was a trailblazer in the development of training films for the U.S. military.

Fleischer was born in 1883 in Kraków and raised in New York City. After attending the Cooper Union School of Art and the Art Students League of New York, he landed a $2-a-week job as a copy boy at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and before long became the newspaper’s staff cartoonist. Another cartoonist there, John Randolph Bray, would open the nation’s first animation studio in 1914 and give Fleischer his start in the fledgling industry.

As the United States inched closer to entering World War I, Bray decided to pitch the U.S. Army on the idea that it could train soldiers faster and better with animated shorts. After meeting with army officials at West Point, Bray secured a contract to make training films for the military. Many of the films would rely on the Rotoscope, a device Fleischer had invented that allowed animators to produce lifelike movements by tracing over individual frames of live-action footage. (Fleischer would be awarded a patent for the device in 1917.) When the army tried to draft Fleischer, Bray protested, reportedly asking, “How can I make films when you draft all my men?”

Army officials evidently saw Bray’s point, and in 1917 Fleischer was relieved of regular service so that he could go to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and supervise the production of the first animated training films under Bray’s contract for the U.S. Army, among them “How to Read a Contour Map,” “How to Fire a Rifle Grenade,” “Methods of Harnessing Artillery Horses,” and “Submarine Mine Laying.”

After the war, Fleischer returned to New York City, where he rejoined Bray Studios as its production supervisor. But Fleischer yearned to establish his own animation studio, and in 1921 he and his brother Dave established Out of the Inkwell Films Inc., and, later, Fleischer Studios. In 1924 Fleischer released the first synchronized sound cartoon—a sing-along short that employed the “follow the bouncing ball” technique—though Walt Disney is often credited with that innovation for his third Mickey Mouse cartoon, “Steamboat Willie,” which was released in 1928. Fleischer was also the first to combine live action with animation—another innovation Disney would quickly copy.

By 1936 Fleischer Studios employed more than 220 artists—second only in size to the Walt Disney Studios—and was churning out Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman cartoons. In 1941 the Fleischer brothers smoothly pivoted to wartime themes. “The Mighty Navy,” for example, features Popeye’s first appearance as a sailor in the U.S. Navy—in the dress whites and black neckerchief he would wear for the rest of his onscreen career. (Popeye’s can of spinach also makes its debut in the cartoon.)

Fleischer’s business relationship with Paramount Studios (his studio’s financial partner and distributor) worsened, however, and his artists were drafted by the dozens into military service. In 1941 Paramount forced Fleischer out, and he joined the Detroit-based Jam Handy Organization as head of its animation department, overseeing the firm’s production of training films for the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy. Fleischer was also involved in a top-secret military project for an aircraft bomber sighting system and in 1943, according to one newspaper account, was sent on a military mission “somewhere in an isolated part of Australia” to photograph and record the activities of a U.S. Army unit.

Fleischer apparently was still involved in making top-secret training films for the U.S. Navy as late as 1956. He died at the Motion Picture Country House in Los Angeles in 1972 at age 89.

Astonishingly, no biography of this industry giant appeared until 2005, when the University of Kentucky Press published Out of the Inkwell: Max Fleischer and the Animation Revolution. Its author: Richard Fleischer, who died the following year.

—Bill Hogan, Editor

his article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.