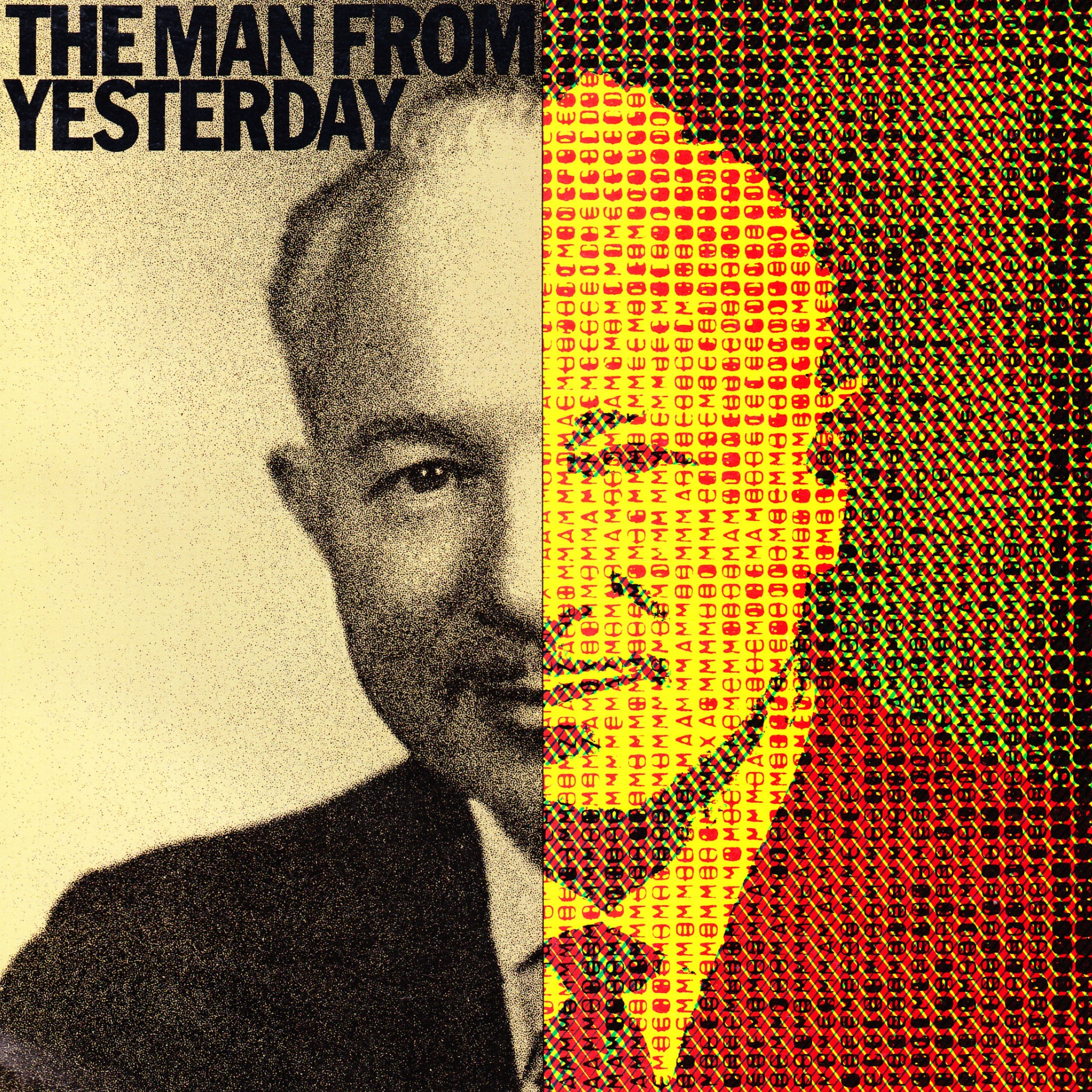

The Man From Yesterday

UP ON MICHIGAN AVENUE, N.E., where Washington’s battered buses once rumbled into huge garages for a night of rest and rehabilitation, the machines, materiel, and manpower are quietly being readied. Inside these cavernous quarters, an impressive array of sleek state-of-the-art equipment — some of it said to be one of a kind — has been assembled, tested, and retested. The components of this futuristic facility stand idle now, awaiting only a simple go-ahead from headquarters and a stream of electronic instructions from a central computer.

Since the inception of this project, code-named DCTECH, more than a year ago, its exact mission has been something of a mystery. Outsiders are not permitted to see what’s going on inside without the approval of the commander-in-chief. Millions of dollars already have been spent, and hundreds of millions more are at stake. So, too, is the technological superiority, and perhaps even the very survival, of an industry that America’s national defense cannot do without.

The operation’s command post is nearly five miles away, in a three-story red brick building with a commanding presence at the Key Bridge entrance to Washington. In recent years the building has housed, among other things, research projects funded by the U.S. government and Georgetown University. When the telephones inside 3600 M Street, N.W, ring, they are answered, “Ninety-seven hundred.” This is the only way, apparently, to reach the operation’s commanding officer — a man once known by his troops as “the Superchief.”

No one, however, calls him Superchief any more. They call him Mr. Chalk.

As names in the nation’s capital go, O. Roy Chalk’s is well-known. His reputation, for better or for worse, precedes him. Most Washingtonians remember Chalk as the last private owner of the District of Columbia’s bus system, which was commandeered by the city 12 years ago, and as the flamboyant proprietor of — and boldest — gambit of his business career. He is trying to deal himself into the high-stakes game of high technology: semiconductors, software, CAD/CAM, fiber optics, laser beams, robotics. There’s money to be made in wave-of-the-future technology, and Chalk, as always, is looking for a piece of the action.

Since early 1983 Chalk has been methodically laying the groundwork for a full-scale assault on what many experts believe will emerge as the most lucrative niche of the machine-tool industry: flexible manufacturing systems. By marrying space-age technology with machine tools, flexible manufacturing systems can move engineering designs — or even mere ideas — from the drawing board to reality with astonishing speed, efficiency, and accuracy.

Chalk has been promising, in effect, to do for the American machine-tool industry what Lee Iacocca did for Chrysler.

Like Iacocca, Chalk has welcomed adulation, or at least attention, and he has, at one time or another, had plenty of both.

Within Washington’s buttoned-down business community, he was a bona fide maverick, perhaps even the Potomac’s premier riverboat gambler. (He reportedly arrived at some business decisions by rolling a pair of lucky brass dice that he carried in his pocket.)

Ever since his arrival in Washington in 1956, Chalk has operated his businesses as a kind of one-man band. “I couldn’t afford to hire enough men like myself,” he once said, “so I have to do it myself.” Consequently, Chalk has rarely shown any reluctance to toot his own horn. “He struts around,” an acquaintance told a newspaper reporter in 1965, “like a guy unveiling a statue of himself.”

These days, however, Chalk is keeping something of a low profile. Through an assistant, he agreed, and then declined, to be interviewed for this story; he also declined to grant Regardie’s permission to see DCTECH’s facility.

Chalk has installed some of the most advanced machine-tool equipment money can buy — equipment reportedly worth between $5 million and $10 million — within the DCTECH facility. An expert who has been inside DCTECH says Chalk’s layout is formidable. “The equipment that is pulled together at DCTECH,” says Anthony Bratkovich, the engineering director of the National Machine Tool Builders’ Association, “is state-of-the-art equipment.”

And Fred L. Haynes, a Commerce Department official who has advised Chalk along the way, is emphatically enthusiastic.

“In terms of the facility itself,” he says, “it probably is not duplicated outside of the defense-industrial complex.”

But perhaps Chalk has good reasons, this time, for playing his cards so close to the vest. As he nears 78, he may be on the verge of closing the most astonishing deal of his career.

CHALK HAS BEEN one of Washington’s most enigmatic entrepreneurs for nearly 30 years. In the old days, as a self-made millionaire with something of a Midas touch, he acquired everything from apartments to airlines at bargain-basement rates, disposing of them later at penthouse prices. He saw profits in everything (even in New York City’s subway system, which he once offered to buy).

He started in real estate in the 1930s. As a young lawyer in New York City, he drew one enduring lesson from representing clients in real estate transactions: prime properties, he discovered, could be acquired with next to no cash.

After buying an apartment building in the Bronx, Chalk shifted his attention to Manhattan and zeroed in on Fifth Avenue. He engineered some spectacular deals. One of the sweetest was the purchase of a 15-story apartment building on Fifth Avenue at 82d Street, directly opposite the Metropolitan Museum of Art and overlooking the lagoons of Central Park. He paid $1 million for it in 1942.

Chalk closed the deal with only $50,000 of his own money; the rest of the cash he needed came from a $150,000 second trust and a $50,000 bank loan. If the deal seemed too good to be true, it wasn’t; many more like it were to follow.

In 1945, as World War II ended, Chalk branched out into the aviation business. He bought two war-surplus DC-3s for $5,000 apiece, had them converted for civilian operation, and started the first nonscheduled independent airline, Trans Caribbean. Chalk soon found himself at war with Pan American over fares to Puerto Rico and back. To boost business for his San Juan-to-New York service, he offered discount fares ($45 one-way), free box lunches, and in-flight entertainment. There was no end to Chalk’s ingenuity. “We used to send salesmen out on donkeys into the mountains to find passengers,” he once recalled. “We brought the passengers back on the donkeys.”

Within a few years Chalk had acquired an enviable reputation; he was seen as an entrepreneur extraordinaire, a businessman who could smell a good deal a mile away and close in before anyone else got wind of it. (Chalk’s reputation, apparently, extended well beyond the United States; in 1949 he was granted a private audience with Pope Pius XII.)

In 1956, acting on a hot tip, Chalk closed the best, and perhaps the most important, deal of his career. With a down payment of only $500,000, he acquired the assets — lock, stock, and barrel — of Capital Transit Company, which operated Washington’s streetcar and bus lines. He financed the rest of the purchase price, amounting to a little more than $13 million, with a $9.1 million loan from Chase Manhattan Bank and a mortgage on the balance from Capital Transit itself. The transit company had become so unpopular during a 57-day strike in 1955 that Congress had revoked its franchise. As the headaches of operating the system intensified, Louis Wolfson, who controlled Capital Transit, became especially anxious to get rid of the company and get out of Washington.

At the time Chalk took over, Capital Transit’s bank accounts bulged with cash — a reported $7.6 million. Four months after the deal went through, Chalk used some of that money ($5.6 million, by one account) to repay the lion’s share of the bank loan. Using revenues generated by the company itself, he was able to repay the rest three years ahead of schedule. For a while the company seemed to be minting money. In less than two years, in fact, its profits easily exceeded Chalk’s $500,000 cash investment.

And this was only part of the good news for Chalk. Capital Transit’s vast portfolio of real estate had been carried on its books at only $2.1 million, but that amount represented only an aggregation of the original purchase prices (some stretching back as far as 1862) plus the depreciated value of the buildings.

For years Chalk’s stewardship of the company, which he renamed DC Transit, seemed like a long-running, happy extravaganza. He handed out gold-plated bus tokens. He painted the entire fleet of buses and streetcars a new shade of green, and he accented them with a bright streak of flamingo pink. He put stewardesses on some of his deluxe streetcars. He advertised.

Chalk was full of ideas for advancing mass transit in the nation’s capital. He once advocated that automobiles be banned from Washington’s streets, at least during rush hours, so that DC Transit could take everyone for a ride. In 1958 he announced plans to build a $35 million tourist, business, and cultural center on Washington’s Southwest waterfront, with monorails running to the Capitol and the Pentagon and helicopter service to other points. He predicted in 1960 that “ground-effect” vehicles, riding on cushions of air, would be ready to replace buses in another five years. And in 1966 he speculated that DC Transit might, within the next year and a half, have the prototype of a new atomic-powered bus on Washington streets.

Chalk even offered to buy New York City’s subway and bus system for $615 million, with $110 million down, but there were some strings attached: he wanted a 49-year franchise to run it at a guaranteed net profit of 6.5 percent. A special committee appointed by New York City mayor Robert E. Wagner studied Chalk’s proposal but concluded that the transit system was worth 10 times what Chalk wanted to pay. The committee’s report called Chalk’s terms “fantastic, having a fairyland quality quite unrelated to the realities of transit in New York City.”

All the while Chalk kept up his customary, and frenetic, pace of wheeling and dealing. He acquired established enterprises and created new ones so quickly that few people could keep up with his catalog of companies. He wined and dined VIPs as if there were no tomorrow; in August 1964, for instance, he anchored his private yacht, Blue Horizon, offshore at Atlantic City and welcomed aboard batches of bigwigs attending the Democratic National Convention. Later that year columnist Drew Pearson of Washington Merry-Go-Round fame wrote: “The most successful lobbyist in Washington remains O. Roy Chalk, the DC Transit czar.”

Chalk’s widespread popularity in Washington, however, was already waning. The last of the city’s streetcars had been put out to pasture in 1962; many passengers blamed Chalk, even though he had been forced by law to replace the streetcars with buses. Deteriorating service and a series of fare increases didn’t help matters, particularly in view of Chalk’s lifestyle; he owned not only yachts but Cadillac limousines and Rolls-Royces. So while Chalk traveled in style, commuters came to feel that they were paying more and enjoying it less.

As for Washington’s proposed subway system, the public and politicians loved it. Chalk hated it. No one seemed to salute the idea he ran up the flagpole, which was for taxpayers to finance the construction of the new Metrorail system and then turn it over to him. (After all, Chalk said, he didn’t pay for the roads his buses ran on.) As a result, he opposed the project with considerable vigor, but only until it became clear that he could not stop it. He threw in the towel in 1966, declaring himself a “100 percent” supporter of the subway.

By the late 1960s Washington, like most other major cities across the nation, decided that instead of regulating the local bus company, it might as well own it. Chalk, faced with declining ridership, increasing costs, and DC Transit’s bumpy bottom line, did not oppose the concept. The only sticking point, really, was how much he would be paid for it.

In his negotiations with Washington’s Metro authority, Chalk claimed that the value of his transit company was as much as $75 million — more than five times what he had paid for it. The two parties reached an impasse. Chalk reportedly demanded more than $60 million; Metro would offer no more than $38.2 million, the value established by an appraisal firm it had hired.

The negotiations sputtered and then broke down. And so at 2:00 a.m. on January 14, 1973, Metro took control of the bus lines through condemnation proceedings. Chalk was able to keep some $20 million worth of real estate in and around the nation’s capital — buildings and property that Metro’s officials said were not needed to run the bus lines.

Since losing control of Washington’s bus system, Chalk has presided over his business interests as chairman and chief executive officer of DC Trading and Development Corporation. Although DC Trading and Development’s stock is publicly traded (the company has about 5,000 shareholders), there’s no doubt who runs the show; Chalk and his wife own roughly one-third of the outstanding shares. DC Trading and Development has been a kind of holding company for an eclectic assortment of Chalk enterprises, which have included a travel agency, an airline with no airplanes, and an effort to resuscitate an old gold mine in California’s Sierra Madre mountains. Up to now though, DC Trading and Development’s main business has been owning and developing real estate — real estate left over from DC Transit’s vast portfolio of properties, ranging from choice rights of way to a sprawling country estate.

Chalk has specialized in seizing sure things throughout most of his career. “I never pay more than 40 percent off,” he once boasted, meaning that he searched for deals in which the actual value of a property (or a company) far outstripped the asking price.

Today Chalk seems to be entering the riskiest kind of business imaginable. Yet in characteristic fashion, he has managed to cover his bets.

THE AMERICAN MACHINE-TOOL INDUSTRY, to put it charitably, has been ailing. Manufacturers of industrial equipment are just now emerging from the worst depression they have seen since the 1930s. The machine-tool industry, in fact, is in such bad shape that it has been trying to check itself into the federal government’s economic emergency ward.

In recent years its vital statistics have not been encouraging. In 1982, for example — one of the industry’s worst years — the total sales of machine tools in the United States were $3.6 billion. In 1983 cuts in capital spending brought on by the recession helped slice even that discouraging level of output in half, to $1.8 billion. In 1984 the output inched up to $2.3 billion.

The other major factor in the industry’s decline has been an influx of imported machine tools. Through the first half of 1984, for example, imports accounted for more than 37 percent of the new machine tools installed in the United States.

The villains, as some see it, are the usual suspects. Japanese manufacturers — the big names are Toyoda Machine Works, Ltd., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd., and Tsugami Corporation — have been accused of using big discounts and generous financing terms to penetrate deep into U.S. markets. Some American machine-tool builders, including Bendix, Acme-Cleveland, and Litton Industries, have decided, in effect, that if they can’t beat the Japanese, they’ll join them. Bendix, for example, sells Japanese-made machining centers in the United States under the name Bendix-Toyoda.

There is, however, a glimmer of bright light on the industry’s horizon. And it was enough, apparently, to catch Chalk’s eye. Older machine-tool layouts are already giving way to the best high-technology has to offer: flexible manufacturing systems. FMSs, as they’re called, make the whole notion of retooling obsolete. A state-of-the-art FMS — a series of advanced machine tools connected by automatic handling equipment and driven by a host computer — can even eliminate the drawing board.

Consider, for a moment, the lowly widget. In an FMS, CAD/CAM (computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing) technology creates engineering specifications for the widget on a computer screen (perhaps, even, with no human help) and stores them in the computer’s memory. Then, highly sophisticated software directs the movement of the widget through the various components of the FMS, using advanced robotics to guide it from point A to point B and so on, untouched by human hands. In an FMS the software is everything; it’s the maestro leading the factory’s high-tech orchestra.

Now add another part — a framus, say — to the equation. In the old days a factory needed to manufacture hundreds or even thousands of widgets in a single production run before it could move on to manufacturing any framuses. The widgets and the framuses went into inventory and if design changes were later needed . . . well, there went the inventory.

In an FMS, all of the tooling and tinkering processes are neatly stored away, to be called up or changed on short notice. Production runs, accordingly, can be kept consistent with need or demand. The beauty of it all is much more than skin-deep.

“Until the microprocessor came along and was related to productive machinery, all of this would have been a pipe dream,” says Dick Priebe, the director of corporate affairs for Cross & Trecker, one of the leading U.S. manufacturers of FMSs. “The whole key, really, is to have the internal software capability of writing the programs that make unmanned machines possible.”

Little wonder, then, that FMSs are the hottest tickets going in high technology. Some industry analysts predict that the market for FMSs may reach $1 billion annually by 1990.

Little wonder, too, that Chalk saw something interesting in all this.

As far as anyone seems to know, the leading purveyors of FMSs have marketed, designed, and installed the systems only for individual manufacturers. “In all probability, no job shops have gone the FMS route,” says David Sutliff, an analyst for Salomon Brothers. “It’s just a little bigger bite than they’re willing to take on.”

“To my knowledge,” says Priebe of Cross & Trecker, “there is no job shop, per se, in the country able to take work in from a whole variety of manufacturers which is completely automated and able to run parts at random on real time.”

Hughes Aircraft, in other words, may have a state-of-the-art FMS, but it can hardly be expected to use it to manufacture spare parts for Boeing, General Dynamics, or any other company in the industry.

Chalk’s idea, in a nutshell, is to make highly advanced FMS technology available to many different companies — to offer, in effect, an automated job shop that will make spare parts on call — and then to license technological breakthroughs developed at DCTECH to anyone who’s willing to pay a price for progress.

Chalk also has sought to portray DCTECH as a vehicle for injecting new competitive clout into the U.S. machine-tool industry. Yet because DCTECH has no American-made equipment, save for two computer controls — everything else was made in Japan or Italy — some within the industry are a bit skeptical of Chalk’s claims. And no one seems to know DCTECH’s actual mission. “Every time that I have been present at a meeting where Chalk has been there, the specific research agenda had yet to be discussed in any concrete terms,” says Kim McCarthy, the legislative director of the National Machine Tool Builders’ Association. And though Chalk has talked with executives of major machine-tool manufacturers, McCarthy emphasizes that “DCTECH is in no way a machine-tool-industry-sanctioned initiative.”

Chalk’s idea, nonetheless, is nothing short of brilliant. Relatively few manufacturing companies in the United States have yet seen the wisdom of FMS technology, which requires considerable chunks of capital. A small-scale FMS costs a few million; a full-fledged “factory of the future” might cost $20 million or more. And before manufacturers make that kind of investment, they want to be absolutely certain that they’ll get their millions’ worth.

And if they’re not willing to buy the technology, Chalk reasons, they just may be willing to “rent” it from DCTECH.

There is, however, a big question mark looming over DCTECH’s prospects, and it’s likely that even Chalk does not know the answer. What, exactly, will DCTECH do, and who, exactly, will be its customers?

THE FIRST PUBLIC INKLING of DCTECH Research Centers, Inc., came on September 14, 1983 with a display advertisement in the Washington Post headed RESOURCES AVAILABLE FOR HIGH-TECH PRODUCT RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT & MANUFACTURE. The text noted, in part: “DCTECH is looking for small/medium-sized companies with advanced products needing further research, development, manufacturing facilities, engineering expansion, marketing assistance, or financial resources. Working closely with an R&D consortium of leading universities and a reservoir of professional scientists, DCTECH is interested in joint ventures, mergers, or acquisitions” in fields ranging from robotics and semiconductors to genetic engineering and underwater acoustics.

To those familiar with Chalk’s operations, the ad had something of a surprising ring to it. For one thing, DCTECH’s parent company, DC Trading and Development, hardly seemed to be in any position to provide “financial resources” for such ambitious projects; most of its operations were losing money, and the company was on its way to posting a $787,464 loss for 1983. (Moreover, in a matter of months the Internal Revenue Service would assess DC Trading and Development for a net tax deficiency of more than $2 million stemming from its audits of the company’s amended federal income tax returns for 1973, 1974, and 1978.) And any talk of “joint ventures, mergers, or acquisitions” seemed just a bit premature; at the time, DCTECH consisted, more or less, of an untested idea and an empty bus garage.

Shareholders of DC Trading and Development learned of the new high-tech subsidiary through the company’s annual report for 1983. It informed them that DCTECH was being created to “manufacture spare parts and to conduct research in support of the machine-tool industry,” that the old Brookland Garage was being converted into a “manufacturing research facility,” and that more than $3 million worth of advanced machining equipment had been secured for purchase or lease with a 10 percent deposit.

The company’s shareholders were also informed of another deposit, for $100,000, that had been placed with McDonnell Douglas Corporation in early 1983. The deposit had accompanied a letter of intent from DC Trading and Development to purchase a new DC-10-30F convertible freighter at a price of $42 million. Shareholders may have wondered why, but the matter was moot by the time they learned of it: in June 1983 McDonnell Douglas had returned the money.

In recent years DC Trading and Development has not been in the best position to take business risks. From 1981 to 1983, the last three years for which financial figures are available, Chalk’s company posted losses in two. Its losses, in fact, outstripped its total earnings (primarily from property rentals and from interest on mortgages and investments) by more than $1.1 million. What’s really kept DC Trading and Development cranking has been “special income” — money, for the most part, won in court by contesting the District of Columbia’s position in condemnation proceedings for company-owned property. In 1983 it received nearly $4.3 million as part of a court-awarded judgment (totaling $6.75 million) for its right of way along the old Cabin John trolley line; the year before, it had collected just under $2.5 million for the same land in condemnation proceedings. This valuable sliver of real estate was carried on the company’s books at $201,000.

The company has been mired in litigation for another reason. Most Washingtonians have long forgotten a series of fare increases by DC Transit shortly before it was taken over by the city, but a few tenacious lawyers have not. They’ve been seeking to wrestle money away from DC Trading and Development by arguing that DC Transit’s final fare increase (from 32 cents to 40 cents) generated excessive profits. They’ve also argued that DC Transit’s riders, not its shareholders, should have benefited from the vast appreciation in its real estate portfolio. For years the question hasn’t really been whether DC Trading and Development will have to pay restitution to riders, but how much.

Over the years the seriousness of the litigation has been such that the company’s accounting firm, Leopold & Linowes, has seen fit to include this standard disclaimer in its reports to shareholders: “Should the decisions be adverse to the Company, the amounts awarded could be substantially in excess of the Company’s stockholders’ equity, and therefore could have such adverse effects as to preclude the Company’s continuance as a viable concern.”

IF DCTECH TURNS OUT to be little more than a high-tech crapshoot — and there is every indication that it is just that — Chalk has, quite ingeniously, tried to guarantee that its parent company won’t be left out in the cold. In fact, DCTECH may bring DC Trading and Development the one thing it has frequently lacked in recent years: profitability.

Chalk’s plan is brilliant because it is nearly foolproof. Even if DCTECH is a colossal failure — a high-tech white elephant — Chalk won’t need to lose much sleep over it. He will be a much wealthier man than he is today.

Chalk will owe the value added to a relatively new scheme that has been aggressively promoted by the Reagan administration as a way for U.S. industries to maintain their competitive edge in the face of unprecedented foreign competition. It’s called the research and development limited partnership, and it allows individual companies, or batches of them, to attract capital from wealthy speculators who are on the lookout for a valuable fringe benefit in their investments: a highly leveraged tax shelter. Critics of the limited partnership approach, in fact, say that it has more to do with tax avoidance than with research and development.

Bruce Merrifield, the Commerce Department’s assistant secretary for productivity, technology, and innovation, has been the Reagan administration’s point man for R&D limited partnerships. To compete with foreign companies, he has argued, big American firms need to be able to pool their R&D money without worrying about running afoul of the nation’s antitrust laws. His vehicle for accomplishing all this has been the research and development limited partnership.

RDLPs have shown phenomenal growth in recent years. The Commerce Department keeps track of public syndications, and its figures show that the aggregate value of publicly syndicated RDLPs zoomed from $23 million in 1980 to $916 million in 1984.

And that’s only part of the picture. There’s no way to keep tabs on private offerings of RDLPs, but Haynes, who works for Merrifield at the Commerce Department, suggests that they, too, have exploded. “We kind of take as a rule of thumb,” Haynes says, “that the private placements probably equal what the public syndications were.”

With nearly evangelistic fervor, Merrifield has pushed the RDLP concept on virtually anyone who will listen. Chalk happened to be one of those listening.

“I think Chalk heard the assistant secretary speak about the potential of applying RDLPs as a vehicle for bringing new products to commercialization and doing it relatively inexpensively with a new financing scheme,” Haynes says. “Chalk heard about it, asked for some assistance, and very carefully followed the guidelines that we provided, which are available for sale through the National Technical Information Service. Then Mr. Chalk just took those and followed them to the letter, got clearance from the Department of Justice on his plans, and had several organizational meetings. And because he believes so strongly in the operation, he, out of his own funds, actually created the factory that we have now called DCTECH.”

By early 1984 Chalk had prepared a prospectus for DCTECH Research Center Partners, Ltd., an RDLP designed, ostensibly, to bring technologically advanced machine-tool systems to market. And later in the year, on October 15, Chalk secured a go-ahead from the Justice Department’s antitrust division.

By the end of February 1985 Chalk had not filed a registration statement for any DCTECH limited partnership with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which the law requires for public syndications. As a result, it is not yet possible to predict the final form of the limited partnership with any certainty. But a draft of its prospectus, which Chalk submitted to the Justice Department in connection with his request for antitrust clearance, outlines its proposed terms and provides a number of revealing glimpses into exactly what he has in mind.

If successful, the DCTECH limited partnership would raise nearly $220 million from investors, whose minimum investment would be $25,000 over three years. “Although the Partnership is not intended primarily as a tax-oriented investment vehicle,” the draft of the prospectus notes, “it is anticipated that the IRS will consider the Partnership and its proposed activities to be a tax shelter.”

Under the terms of the draft prospectus, DCTECH Research Centers, Inc., a subsidiary of DC Trading and Development, would be the general partner. It would also be the contractor. This means, in essence, that DCTECH would be hiring itself to carry out the research and development contract on behalf of the partnership.

Such a nifty arrangement poses obvious conflicts of interest. The prospectus notes, for example, a particularly important one: “While the development contract stipulates that the Partnership shall pay specified compensation for research on and development of the technologies, such compensation has been determined by negotiations between the General Partner and DCTECH, which might not be considered to be arm’s-length negotiations.”

This, of course, is a magnificent understatement; a party cannot negotiate with itself, by definition, from arm’s length.

So how much money would DCTECH be able to pay itself? That, the draft prospectus says, is a murky question: “The actual amount to be paid under the Development Contract, and the amount of profit to be realized by the Contractor, if any, cannot be determined at this time.”

The draft prospectus goes on, however, to paint one possible scenario. “The maximum amount to be paid to the Contractor under the Development Contract,” it says, “would amount to substantially all of the net proceeds from this offering, the amount of the General Partner’s capital contributions, and all interest and income earned thereon.”

Chalk’s DCTECH Research Centers, in short, could wind up with the whole ball of wax — something in excess of $200 million. That would be a juicy contract for any business, but particularly for a company with no track record and no expertise in research and development. (Chalk was involved in the machine-tool business once before. In 1943 he started up a small manufacturing company in New York to make metal parts, mostly machine stampings, as a subcontractor on Defense Department jobs.)

And what would investors in the DCTECH limited partnership get — beyond, of course, some favorable tax treatment? This is also a murky question, in part because research and development is supposed to be risky. The draft prospectus contains this warning to investors: “Even if the designs of the technologies are completed and result in prototype systems, there can be no assurance that the systems can be manufactured, marketed, and serviced.”

Stripped of all of its legal mumbo jumbo, the DCTECH limited partnership plan represents nearly a no-lose proposition for Chalk. Beyond the quick financial fix that DC Trading and Development would derive from such a huge injection of cash, there are some long-range pluses too. And it should come as no surprise that Chalk would be the leading beneficiary.

Chalk and his wife, Claire, own nearly one-third of DC Trading and Development’s common stock — roughly 750,000 shares. If one of the company’s subsidiaries — DCTECH, for example — signs a contract guaranteeing an entirely new revenue stream, its stock — recently trading at $3 to $3.25 a share — can reasonably be expected to increase in price. And even a 50-cent increase in the price of DC Trading and Development’s stock would increase the value of the Chalks’ holdings by more than $300,000.

Finally, and perhaps most significant, the terms of the draft prospectus would allow Chalk to economically develop a number of properties in DC Trading and Development’s portfolio. While the prospectus spells out in great detail some of the potential conflicts of interest — revolving principally around DCTECH’s dual role as general partner and contractor — it does not alert potential investors to what might emerge as the biggest bonus of all for Chalk: tens of millions of dollars, and maybe more, for developing old DC Transit real estate.

One DCTECH brochure is particularly illuminating in this respect. “DCTECH Research Centers, Inc., is developing its own property for Research, Development, and Engineering Facilities,” it says. “These properties cover over eight acres in highly visible locations within the District of Columbia. These four sites have over 300,000 square feet of floor space.”

Moreover, these four properties seem to have only one thing in common. All of them are owned by subsidiaries of DC Trading and Development. They are:

♦ The former Brookland Garage at 10th Street and Michigan Avenue, N.E., which now houses DCTECH’s prototype flexible manufacturing system. “Future expansion plans include the addition of a multistory building at the front of this property,” the brochure says.

♦ The former DC Transit headquarters (now Chalk’s headquarters) at 3600 M Street, N.W. “The second and third floor will be adapted to research facilities with approximately 40,000 square feet on each floor,” the brochure says.

♦ The former Eckington Car Barn at 4th and T Streets, N.E. No particular purpose is specified for this one-time DC Transit maintenance garage, which has more than 40,000 square feet of floor space.

♦ The old Navy Yard Car Barn covering an entire square block at 5th and M Streets, S.E., which has more than 100,000 square feet of floor space. No particular purpose is specified for this property, which was, until recently, leased to the federal government.

There is, of course, a certain beauty in this plan. DCTECH, as both the general partner and the contractor of DCTECH Research Center Partners, Ltd., would enter into lease or other arrangements for these properties with its parent corporation, DC Trading and Development. Then it would bill the partnership for “lease payments or financing charges, depreciation, and amortization of such facilities and equipment.”

And should DCTECH, as the contractor for the partnership, fail completely in its high-tech mission — “to develop a family of design specifications for new and innovative technologies” — it would still have succeeded in pumping millions of dollars into Chalk’s businesses.

SOMETIME SOON O. Roy Chalk’s master plan for DCTECH will face the test of the marketplace. As any investment banker knows, the timing of a public syndication is everything — and Chalk, apparently, is waiting for just the right time.

Whether Chalk’s in the right place is another question altogether. But that really doesn’t even matter. If the world isn’t ready for DCTECH’s services, or if some other company beats Chalk to the punch, the partnership’s investors will still have their tax deductions. And DCTECH will still have a multimillion-dollar contract of the handsomest kind: an irrevocable contract.

And therein lies an important lesson for anyone who has ever underestimated the amazing O. Roy Chalk. Once again he’s figured out a seemingly foolproof scheme to make money.

“I don’t know where I’m going,” Chalk once said. “I just know I’m going.” The only question now seems to be whether anyone will be joining him for the ride.

Sidebar: Chalk Board

This article originally appeared in the April 1985 issue of Regardie’s.

3600 M Street Acme-Cleveland Anthony Bratkovich Bendix Bendix-Toyoda Blue Horizon Brookland Garage Bruce Merrifield Capital Transit Company Chase Manhattan Bank Claire Chalk Commerce Department Cross & Trecker David Sutliff DC Trading and Development Corporation DC Transit DCTECH DCTECH Research Centers Dick Priebe Drew Pearson Eckington Car Barn Flexible Manufacturing Systems Fred L. Haynes Kim McCarthy Leopold & Linowes Litton Industries Louis Wolfson Machine Tool Industry Machine Tools McDonnell Douglas Corporation Metro Mitsubishi Heavy Industries National Machine Tool Builders’ Association Navy Yard Car Barn O. Roy Chalk Pope Pius XII R&D Limited Partnerships Research and Development Limited Partnership Robert E. Wagner Salomon Brothers Securities and Exchange Commission Superchief Tax Shelters Toyoda Machine Works Trans Caribbean Airways Tsugami Corporation