Letter from MHQ: A Tale of Two Cities

In July 1941, fearing that their city was facing an “unemployment catastrophe,” a group of business, labor, and political leaders from Evansville, Indiana, traveled to Washington, D.C., to ask for an economic lifeline in the form of federal defense contracts. As Roy Morris Jr. tells the story in this issue (“World War II’s Can-Do City,” page 70), the Office of Production Management—which after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would be replaced by the War Production Board—came to the city’s rescue, and almost overnight Evansville was transformed into a hotbed of military production, manufacturing P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers and LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) by the thousands, turning out nearly all of the .45-caliber ammunition used by American soldiers during World War II, and rebuilding and reconditioning countless tanks, trucks, and jeeps.

At the other end of the Hoosier State, however, the city of Elkhart was undergoing its own transformation. Elkhart could rightly lay claim to the title “Band Instrument Capital of the World,” with more than a dozen large manufacturers, chief among them C. G. Conn Ltd., accounting for two-thirds of the world’s entire output of band instruments. Charles Gerard Conn, who had served his country during the Civil War as a soldier in the Union army (rising to the rank of colonel), had perfected a rubber-cushioned mouthpiece for the cornet in 1873 and founded the company that bore his name the same year. It would go on to produce the first American-made cornet (in 1875), the first American-made saxophone (in 1888), and the world’s first sousaphone (in 1898). Conn lured European craftsmen to work in his Indiana factories, and many employees went on to establish their own companies; by 1914, when Conn sold his company, Elkhart was home to some 50 musical instrument manufacturers.

But in 1941 an ominous cloud loomed over Elkhart. “This city is alarmed at the prospects of a war economy,” a reporter for the Indianapolis Star (the state’s largest newspaper) observed, “because it has no allies to help wage a fight before the congressional committees to save its biggest industry from virtual extinction.” A. L. Smith, an executive of C. G. Conn, went so far as to predict that the entire industry would be closed by the end of the year for want of such essential raw materials as steel, nickel, copper, chromium, and other metals; rubber and neoprene; cork; and a host of different plastics.

Smith was only a few months off the mark, and the shutdown of his industry, it turned out, came directly at the hands of Uncle Sam. On May 30, 1942, the War Production Board ordered the production of virtually all musical instruments stopped after June 30 and immediately froze the stocks of 27 types of band instruments in the hands of Conn and other manufacturers as well as wholesalers, stipulating that the instruments be reserved for use by army, navy, and marine bands.

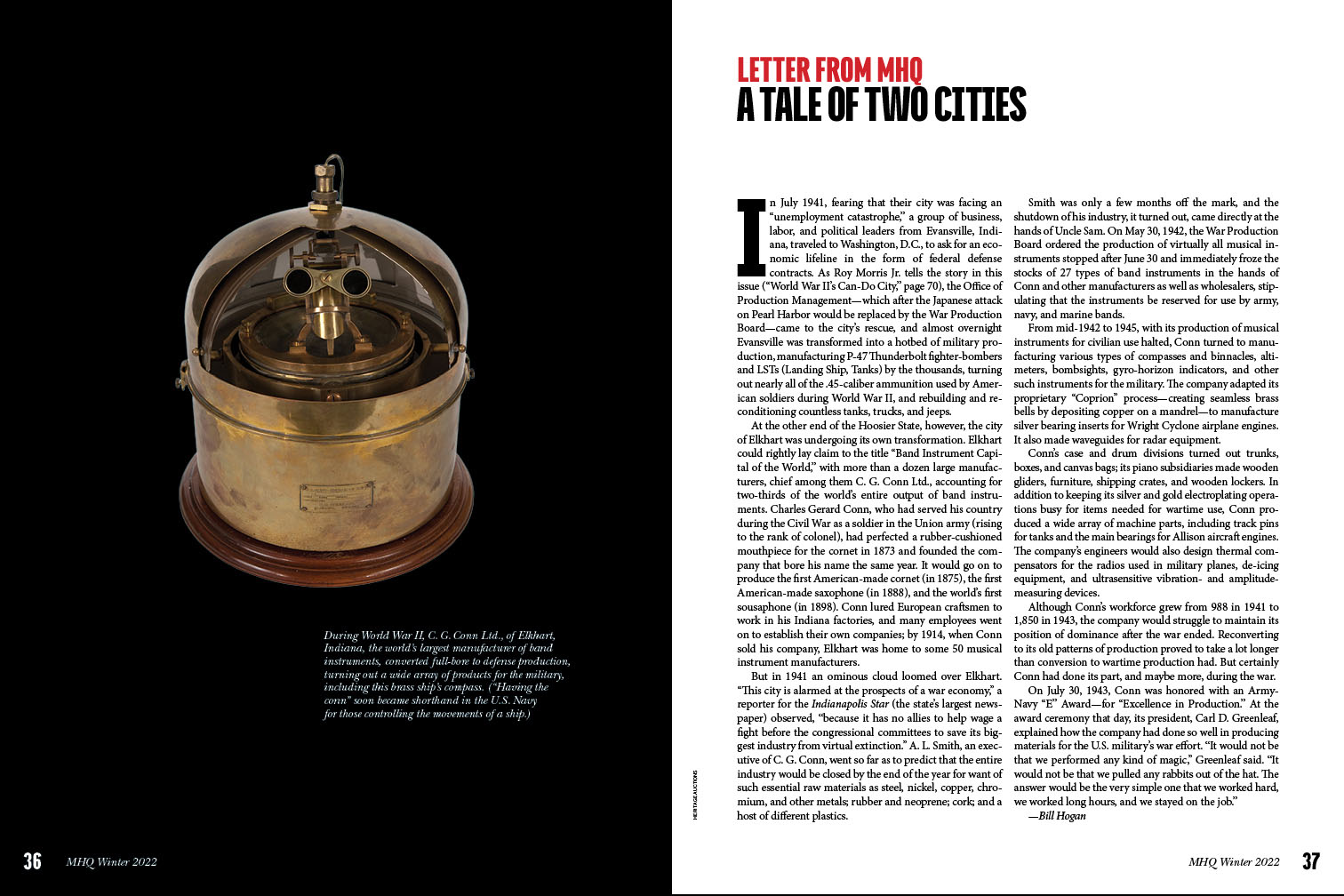

From mid-1942 to 1945, with its production of musical instruments for civilian use halted, Conn turned to manufacturing various types of compasses and binnacles, altimeters, bombsights, gyro-horizon indicators, and other such instruments for the military. The company adapted its proprietary “Coprion” process—creating seamless brass bells by depositing copper on a mandrel—to manufacture silver bearing inserts for Wright Cyclone airplane engines. It also made waveguides for radar equipment.

Conn’s case and drum divisions turned out trunks, boxes, and canvas bags; its piano subsidiaries made wooden gliders, furniture, shipping crates, and wooden lockers. In addition to keeping its silver and gold electroplating operations busy for items needed for wartime use, Conn produced a wide array of machine parts, including track pins for tanks and the main bearings for Allison aircraft engines. The company’s engineers would also design thermal compensators for the radios used in military planes, de-icing equipment, and ultrasensitive vibration- and amplitude-measuring devices.Although Conn’s workforce grew from 988 in 1941 to 1,850 in 1943, the company would struggle to maintain its position of dominance after the war ended. Reconverting to its old patterns of production proved to take a lot longer than conversion to wartime production had. But certainly Conn had done its part, and maybe more, during the war.

On July 30, 1943, Conn was honored with an Army-Navy “E” Award—for “Excellence in Production.” At the award ceremony that day, its president, Carl D. Greenleaf, explained how the company had done so well in producing materials for the U.S. military’s war effort. “It would not be that we performed any kind of magic,” Greenleaf said. “It would not be that we pulled any rabbits out of the hat. The answer would be the very simple one that we worked hard, we worked long hours, and we stayed on the job.”

—Bill Hogan

This article was originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.