Letter from MHQ: Birth of a Notion (or Two)

One of the occupational hazards of editing a magazine, especially one that covers as much thematic territory as MHQ, is that one thing invariably leads to another, and sometimes the backstories we run across are too fascinating to ignore. That certainly was the case with the vintage coin banks showcased in the feature beginning on page 62.

First case in point: “Adolf—the Pig,” a novelty piggy bank that industrial designer Thomas Lamb created in 1942. Lamb hoped that his porcine caricature of Hitler, with its coin-activated noisemaker and the legend “Save for Victory–Make Him Squeal,” would get Americans in the habit of saving their spare change to buy defense bonds.

Lamb, born in 1896 in New York City, was something of a prodigy. At age 7 he became interested in the mechanics of the human body, and at 14, already a talented artist, he found a plastic surgeon who would give him anatomy lessons on weekends in exchange for doing medical illustrations. Lamb was already working on weekday afternoons with a textile designer in an embroidery and lace factory. These real-world experiences led Lamb to drop out of high school to study figure drawing and painting at the Art Students League of New York, and at age 17 he opened his own textile studio. Soon his bedspreads, scarves, napkins, and draperies were being sold in such toney department stores as Lord & Taylor, Macy’s, and Saks Fifth Avenue.

In 1924 Lamb began writing and illustrating children’s books. His first, Kiddyland Story Balloons, led to a contract with Good Housekeeping magazine, a line of Kiddyland textiles and toiletries, and even a Western Union “Kiddygram” that bore Shirley Temple’s endorsement.

Then came World War II.

Lamb, determined to contribute to the American war effort, produced a line of “Victory Napkins” and dreamed up the piggy bank that would become a small-scale sensation, citing Hitler’s resemblance to “a precocious pig” named Pipa he’d met in the country. “Pipa was insulted at first at this comparison,” Lamb later recalled, “but I managed to persuade him to pose for me, and he served as my model.”

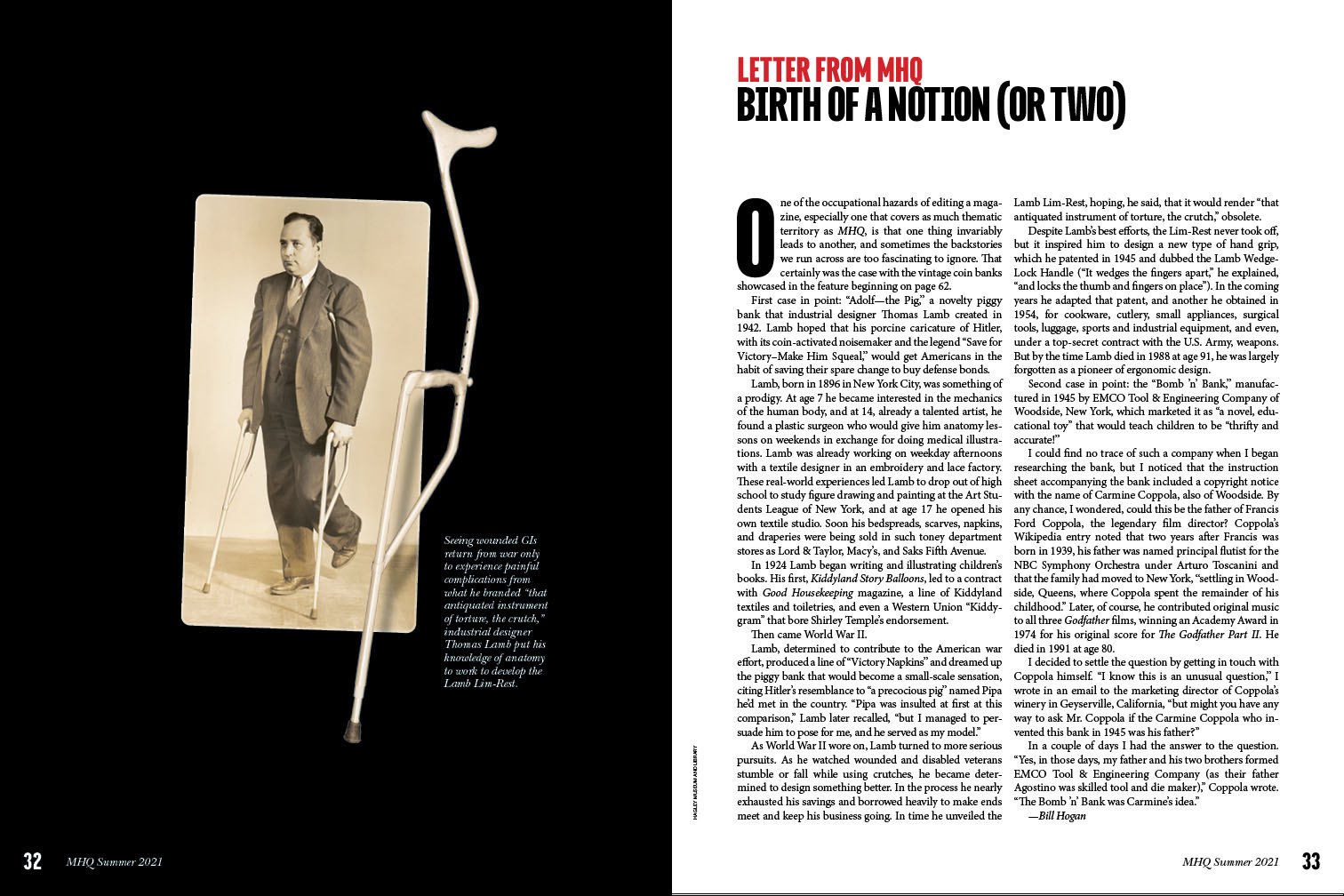

As World War II wore on, Lamb turned to more serious pursuits. As he watched wounded and disabled veterans stumble or fall while using crutches, he became determined to design something better. In the process he nearly exhausted his savings and borrowed heavily to make ends meet and keep his business going. In time he unveiled the Lamb Lim-Rest, hoping, he said, that it would render “that antiquated instrument of torture, the crutch,” obsolete.

Despite Lamb’s best efforts, the Lim-Rest never took off, but it inspired him to design a new type of hand grip, which he patented in 1945 and dubbed the Lamb Wedge-Lock Handle (“It wedges the fingers apart,” he explained, “and locks the thumb and fingers on place”). In the coming years he adapted that patent, and another he obtained in 1954, for cookware, cutlery, small appliances, surgical tools, luggage, sports and industrial equipment, and even, under a top-secret contract with the U.S. Army, weapons. But by the time Lamb died in 1988 at age 91, he was largely forgotten as a pioneer of ergonomic design.

Second case in point: the “Bomb ’n’ Bank,” manufactured in 1945 by EMCO Tool & Engineering Company of Woodside, New York, which marketed it as “a novel, educational toy” that would teach children to be “thrifty and accurate!”

I could find no trace of such a company when I began researching the bank, but I noticed that the instruction sheet accompanying the bank included a copyright notice with the name of Carmine Coppola, also of Woodside. By any chance, I wondered, could this be the father of Francis Ford Coppola, the legendary film director? Coppola’s Wikipedia entry noted that two years after Francis was born in 1939, his father was named principal flutist for the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini and that the family had moved to New York, “settling in Woodside, Queens, where Coppola spent the remainder of his childhood.” Later, of course, he contributed original music to all three Godfather films, winning an Academy Award in 1974 for his original score for The Godfather Part II. He died in 1991 at age 80.

I decided to settle the question by getting in touch with Coppola himself. “I know this is an unusual question,” I wrote in an email to the marketing director of Coppola’s winery in Geyserville, California, “but might you have any way to ask Mr. Coppola if the Carmine Coppola who invented this bank in 1945 was his father?”

In a couple of days I had the answer to the question. “Yes, in those days, my father and his two brothers formed EMCO Tool & Engineering Company (as their father Agostino was skilled tool and die maker),” Coppola wrote. “The Bomb ’n’ Bank was Carmine’s idea.”

—Bill Hogan

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History.

Caption: Seeing wounded GIs return from war only to experience painful complications from what he branded “that antiquated instrument of torture, the crutch,” industrial designer Thomas Lamb put his knowledge of anatomy to work to develop the Lamb Lim-Rest.