Policy Studies: Buying Life Insurance

THE LIFE INSURANCE GAME

By Ronald Kessler

Holt, Rinehart and Winston

289 pp. $16.95

NO MATTER HOW — OR HOW LONG — you look at life insurance, the laws of averages are not encouraging. If you let an agent inside your home, the chances are 1 in 2 you will wind up buying a policy. The chances are 4 in 5 you will buy a decidedly inferior policy. Then, for every dollar you pay to the life insurance company, you’ll get 41 cents back in benefits. And should you die — the reason, presumably, for having life insurance — your beneficiaries will receive roughly $5,000. A funeral alone may cost more than that.

So why buy life insurance in the first place? That’s a good question, and Washington Post reporter Ronald Kessler sets out to answer it in The Life Insurance Game. His conclusion, at least with respect to whole life insurance, is blunt enough: “If you understand it,” Kessler writes, “the chances are good that you will never buy it.”

Yet this is not a book about how to buy life insurance (Kessler’s chapter on that subject, the book’s last, doesn’t even fill two pages). It’s about the nation’s life insurance industry: how it works, who controls it, why it is so powerful — and profitable.

Kessler’s legwork has paid off: His book is a thorough, skeptical, and eye-opening look at an industry second only to banking in wealth. Much of the problem, as he sees it, is in its principal product: whole life insurance, which accounts for 90 percent of the industry’s incoming premiums. Whole life insurance is more investment than insurance — an investment, it turns out, that is virtually impossible to evaluate. As Kessler shows, consumers have little hope of comparing annual yields, or rates of return — which take into account the time value of money — on different policies. Most insurance companies, of course, like it that way, because it precludes potential customers from rate-shopping and allows them to sell “trust,” not value.

Life insurance, the saying goes, is sold, not bought. The industry’s sales force is formidable: a quarter of a million agents peddle hard enough to bring in 30 million new policies a year. Yet many of them, as Kessler shows, do not even understand the products they sell, frequently make material misrepresentations in the course of their sales presentations, and have a profit motive (higher commissions) in pushing whole life over term insurance.

Nearly anyone can become a life insurance agent, but the business’ dropout rate is high (only 1 in 5 new agents is still selling after four years). The successful ones generally practice the soft sell. Agents of the Acacia Mutual Life Insurance Company, for example, are offered videotaped training courses taught by Edwin O. Timmons, a former professor of psychology at Louisiana State University. They are counseled to tell prospects they would like to “share some ideas” rather than sell a policy. They are schooled in a taming technique called “sponging,” in which empathy is all: The proper response to objections, Timmons teaches, is something along the lines of “I can understand why you say that.”

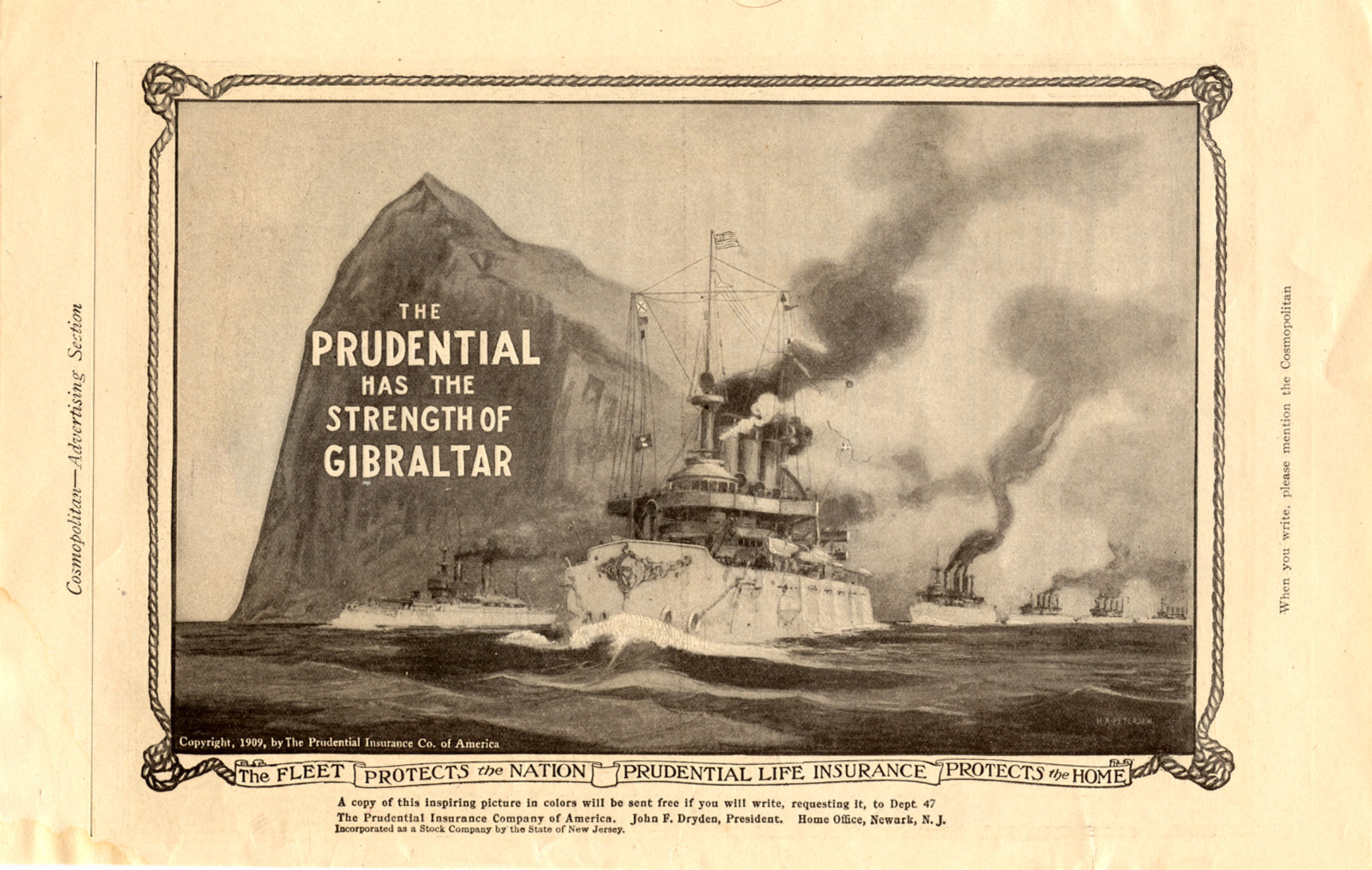

The industry’s bigwigs do not escape Kessler’s gentle, between-the-lines barbs. There is Frank J. Hoenemeyer, for instance, who decides how Prudential Insurance Company wields its wealth. Prudential is the largest life insurance company in the world, and also the richest, with $67 billion in assets. The scope of Prudential’s investment activity is such that Hoenemeyer delegates decisions on smaller matters (anything amounting to less than $100 million) to others. When bigger pieces of The Rock are involved — Is real estate in Houston, say, hot or not? —Hoenemeyer zeroes in on, well, that certain something. “You get a feeling about a city from the people you see on the street,” he explained to Kessler. “What’s their attitude? Do they seem to be walking purposefully?”

READERS MAY DERIVE NO MORE COMFORT from Kessler’s sometimes amusing, sometimes alarming look at the industry’s underbelly. New Enghnd Mutual Life Insurance Company levies a surcharge of $3 per $1,000 of coverage on circus clowns. The bible of the industry, Best’s Insurance Reports, evaluates the cost of life-insurance policies offered by more than 2,000 companies; the worst possible rating assessed by Best’s is “moderate.” And while life-insurance companies collectively ask a firm called Equifax Inc., to investigate some 2 million applicants a year, the effort and expense don’t seem to make much diffference; Kessler found one company that could not attribute a single rejection — out of 5,700 applications — to information dug up by Equifax. (The money the companies spend on this, of course, reduces the benefits they can pay to policyholders.)

Most disturbing of all, perhaps, is the industry’s continued embrace of “industrial life insurance,” which is sold and serviced door-to-door by some 90,000 agents. Eighty years ago, Louis Brandeis called industrial life insurancer “legalized robbery,” and, as Kessler shows, it still is. Because many states impose a $1,000 ceiling on individual policies, some agents load up victims — poor people, more often than not — with dozens of them. Kessler points out that industrial life insurance companies have chalked up collective after-tax profits nearly three times those for the rest of the industry.

In the absence of real federal regulation (there isn’t any), minding the insurance companies is left to the states. Kessler finds that state insurance regulators frequently are lapdogs, not watchdogs, of the industry. Most of the laws they propose, he says, actually are drafted by the industry itself.

With few exceptions, the regulators do not look for complaints; instead, they wait for them to arrive. Very few do. The reason, as a spokesman for the American Council of Life Insurance put it, is simple: Consumers have no way of knowing when they’ve been lied to or cheated.

A persistent theme of Kessler’s book is best summed up by a retired agent for Connecticut General Life Insurance Company. “Whole life,” he told Kessler, “is just a lousy savings plan.”

Most buyers of life insurance, however, have not yet wised up. They’re up against an unaccountable industry selling an inscrutable product. “I don’t use the rate of return because it will confuse people,” another agent told Kessler. “People are looking for someone to guide them in making financial decisions.”

Readers of the The Life Insurance Game may have good reason to feel their trust has been misplaced. This book, in trying to tell the truth about the life insurance industry, may help them even up the score.

This review originally appeared in the March 10, 1985, edition of The Washington Post Book World.