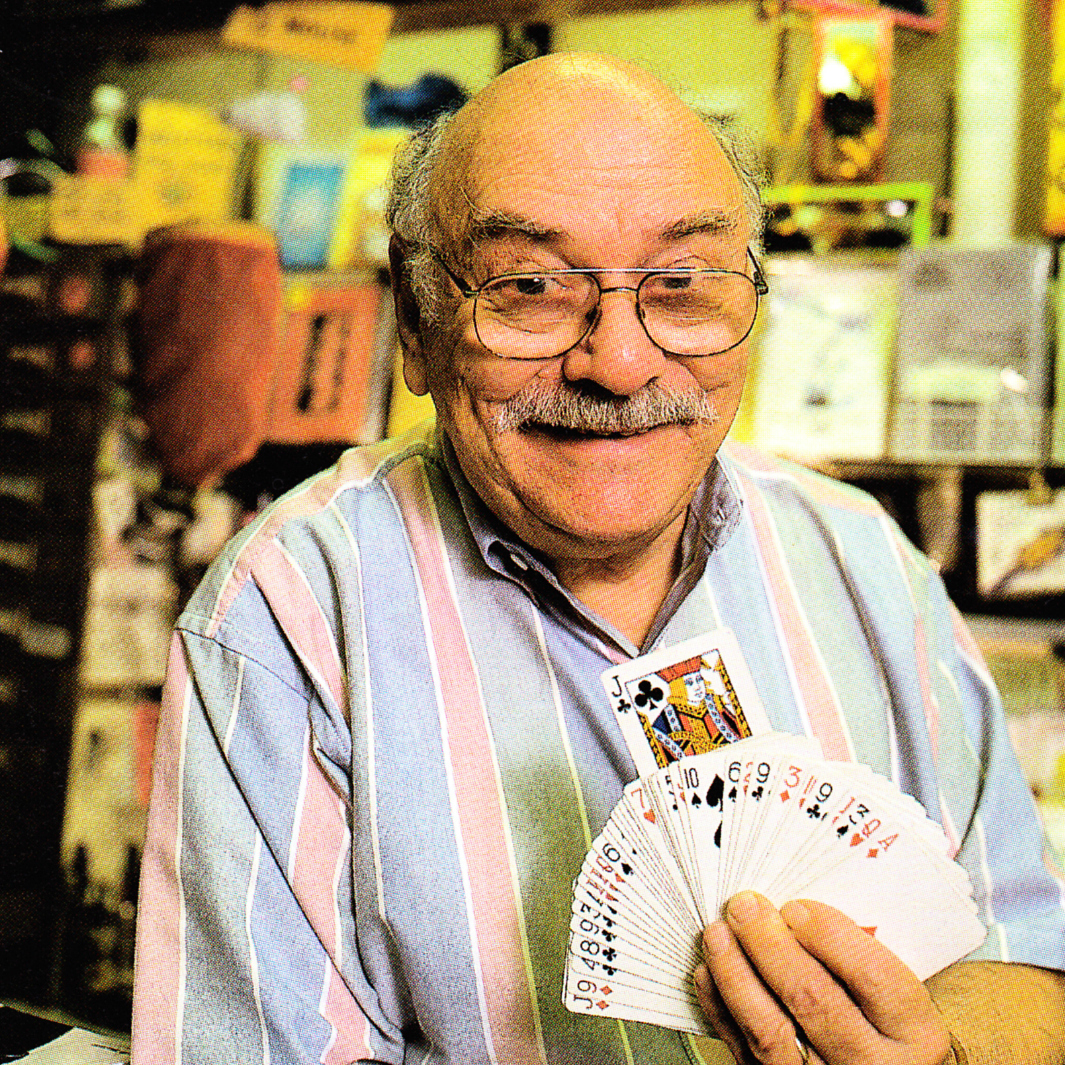

First Person: Al Cohen

MY FATHER STARTED THE BUSINESS IN 1936, when we moved back to Washington from Wilmington, Delaware. My mother was from Wilmington, and my dad was in the jewelry business there.

He opened a little shop at Tenth and D Streets. It was probably twelve feet wide and maybe twenty-five feet long — a tiny little place. Then he met a gentleman who was interested in buying a gift shop that was for sale on Pennsylvania Avenue. The man needed a partner, so they got together and bought the business as a partnership, which they operated together from 1936 until about 1941.

My father had closed the original store, and when his partner, who was an older man, wanted to retire, my dad bought him out. After the war, I came into the business. I’ve been here ever since.

It started out as the Japanese Bazaar. Of course, when we went to war with Japan, you didn’t want to use “Japanese, ” so we changed it to the Oriental Bazaar. We sold everything oriental — Chinese robes, tea sets, ivory. Of course, as that era changed, we couldn’t get those things, and my dad went more and more into the souvenir business. Then we changed it to the National Gift Shop. Washington had become a boomtown, with all the soldiers and sailors coming through, and they all wanted souvenirs.

We always carried a line of novelties and jokes and simple little tricks from a company in New Jersey called S.S. Adams. We carried all their stuff. Back then you could sell card tricks and little coin tricks for ten cents, twenty cents. Dribble glasses, joy buzzers — those things, believe it or not, are as popular today as they were back then. We still sell the dogdonnit and we still sell the rubber chickens, the chattering teeth, and all that stuff. But all the trick matches are gone, all the cigarette loads are gone, because today you can’t sell anything that’s the least bit dangerous.

When I was in college, I roomed with a guy who was an amateur magician, and that sparked my interest in magic a little bit. When I finally came into the business in 1945 or ’46, my dad was partly retired. I had graduated school as an accountant. I had already gotten married and had a baby on the way, and to support a family on a junior accountant’s salary back then was pretty tough. They used to pay you $35 a week. My dad needed help, so I said, “Why don’t I come and help you?” So I did. I still did a little accounting on the side — by then, I had a few individual clients and had started doing some income-tax work. But I came in the business and got fascinated with the magic end of it, and so I started buying more and more excuses to go up to New York and search out the magic distributors up there.

I didn’t consider it a magic shop —we were just like a novelty shop that had some magic, too. But it kept growing and growing and growing. We were located right across from the bus lines that used to come in from Virginia and stop in front of the old Post Office. All the buses would come in and unload there, and we were right across the street.

Back in those years, there weren’t any suburbs, so everybody shopped downtown. The government worked 44 hours a week, including half a day on Saturday. On Saturday, when the government let out, you couldn’t get into a movie theater, you couldn’t get into a restaurant — F Street was like 42d and Broadway, packed with people — you just couldn’t walk.

We used to get a big flow of people all the time. We were a block from the National Theatre, and all the movie houses were a couple blocks up. We also used to get all the show people who were at the National or the nightclubs that were around. We used to get a lot of really good professional magicians and other entertainers who’d come in and hang out in the shop while they had an afternoon off.

It was an interesting, dilapidated old building. It was owned by Christian Heurich, the brewer. Heurich, in those years, was one of the biggest real-estate holders in Washington. The story is that he used to buy corners and that he would lease them to tap bars only if they carried his Senate beer. That was part of his deal: You had to carry his beer.

He was a great guy. When you rented a building back in those years, you had no lease — just a handshake, that’s all. They didn’t do anything for you — no repairs, no maintenance at all. Anything that you had to do in the building you had to do yourself. We did it all — we paid our own water bill, we paid our own electric bill. We paid $200 a month for a four-story building. Can you believe that? Then it went up to $215. And when we finally left there in 1979, I think we were paying $650 a month. And that was it —there were no add-ons at all.

On the second floor of our building there was an old costumer who had everything you could imagine, from Civil War stuff up. On the third floor we had an import-export company. The fourth floor in the building was empty. I think that at one time there were living quarters up there, because there was an old bathroom with an old bathtub. And in the back of the building there was one of those old freight elevators where you pulled a rope and the thing would slowly go up. My brother and I loved it; we used to go there and play on it all the time.

Through the years, the people upstairs either died or moved. So we had these three empty floors up there. Whenever there was an inaugural parade, we had grandstand seats right there. We used to rent out the second floor, put chairs up there, and $10 could buy you a chair to get a perfect view of the whole parade. One year, a really nice guy who worked next door — he was a real character and also a real hustler — came to us before one of the inaugurals and said, “l’ll build bleachers for you up there so that we can get more people to sit.” We had huge windows. He said, “We’ll build bleachers up there so you can rent out like twenty or thirty seats,” and he said, “The only thing I want for it is the food concession I’m going to serve hot dogs and sandwiches and hot coffee.” And we said, “Fine.” So he did that on the two floors, which was very lucrative for us, because we didn’t have to do a thing — he built the thing. We had people who came every four years for an inaugural — they had reserved seats.

When President Kennedy was inaugurated, he came down Pennsylvania Avenue and was waving to us. We thought he was waving hello, but he was actually saying, “We’ve got to get rid of all of these old, lousy looking buildings here” ” Because a few years after that is when they started the redevelopment of Pennsylvania Avenue — which, I guess, in a way, is a good thing — and we got caught up in it.

We were there until 1979. We didn’t have a lease, and the people who had bought the property from Heurich came to us and said: “We’re taking over this building. We’ll give you this much if you get out within a month, and we’ll give you less if you take two months.” In other words, the sooner you get out, the more we’ll compensate you for. Which we took, because there was nothing we could do — we had no lease and couldn’t stay there. So we found another place on H Street, between the 1100 block of H and where the old Annapolis Hotel was; now it’s right behind the Greyhound bus terminal. This was before they built the convention center in 1979. We were there for only one year. We signed a five-year lease with a five-year option, but in the lease there was a thing called a demolition clause. I said to the agent, “What’s a demolition clause?” “Well,” he said, “that’s if they decide to tear the building down, they can throw you out in three months. But they just remodeled the building. They’re not going to tear it down.” Well, it was a big mistake. We moved there, and exactly one year later they came to us and said, “You have to be out of here in three months because we’ve sold the building. You’ve got three months to get out.”

WE MOVED HERE ON JULY 1, 1980. We’ve been here twenty years, but it seems like yesterday — I still remember moving up here. My dad worked in the shop until about 1976. He was born in 1900 and actually came to Washington when he was six months old. He was a great guy; everybody loved him. He was just a very pleasant person, very easy to get along with. My son and I have spats every once in a while, but I never had a spat with my dad. He was that kind of a guy.

My dad had a few little tricks he could do behind the counter. As a kid, he’d helped Howard Thurston on the stage. Thurston would pull up a little assistant from the audience to help him with a trick. People used to ask my dad, “Did you ever go up on stage?” and he’d say, “Yes, I assisted Thurston.”

When he retired, my son, who had graduated college, said, “Maybe I’ll come in with you. I really didn’t want him to, because I thought there were better things in life to do than run a magic shop. He’s been with it ever since.

When I first started selling magic I never felt myself as being a magician — I was just selling tricks. We used to have a theatrical agent named Bob Fried. He was a sightseeing guide, and also a referee and an emcee at Uline Arena, where they used to have wrestling and boxing matches. He was a big guy — very tall, like six-three or six-four, must have weighed 250-300 pounds — with a booming baritone voice. A very interesting guy, and he used to hang around the store a lot. He also did a comedy act. So he comes in one day, and he says, “I booked you for a show.” And I said, “Bob, what are you talking

about? I don’t do shows.” He said: “No, no. I booked you for a birthday party in Virginia. It pays $10, and you have to give me $3 — that’s my commission.” I said, “I’ve got to go to Virginia to do a show?” He said: “It’s good experience for you. You’ve got to do it. ” This had to be in 1948, ’49. I didn’t really want to do it, and I was scared to death. It was just a kid’s birthday party, but I had never performed. Anyway, I did do the show and I had to give him his $3. At first I did one every six months, then it became once a week or so, and then, before you know it, it’s a big thing. I probably did about 3,000 shows. And I kept a log of every show I did — how long I worked, what I did in the show, my comments, what I thought, the miles from the store to wherever it was. I had everything written down on little three-by-five cards.

My stage name was Alfred the Magician. I hated that name, the same way I always hated the name “Al’s Magic Shop,” because to me, it seemed like “Al’s Garage” or “Al’s Barber Shop” or something. When we went into the magic business, I was going to use the name “National Magic Shop,” but there was a company in Chicago called National Magic. So, I said, “Well, I can’t use that name.” We just kind of left it as National Gift Shop, but everybody used to say, ” Let s go down to Al’s magic shop. ” So it started catching on, and I said: “You know what? We’ll just call it Al’s Magic Shop.”

Stan came in around ’74. My wife and I had a big cousin’s club, and in the summer we’d always have a picnic, and all the kids would come in — the typical family thing. So I started doing a magic show for them. Well, after about three or four years, I tell my wife, “You know I’m not doing this anymore.” So Stan says, “I’ll do it.” And he was like twelve years old or something. I said, “How are you going to do it?” He said, “I can do it.” So we went down, and he went through my whole act. He’d been out with me a lot of times in shows. He knew my whole act — with the patter. So he stayed out there and did the whole act, and I was shocked. I really was shocked.

I had a customer, Doc Schiller, who was a retired army colonel. I don’t know where he got the name “Doc,” but everybody called him Doc Shiller and they really thought he was a medical doctor, which he wasn’t. He worked in the government after the service. He used to hang around the store a lot and he was a very, very nice guy. He taught me a lot. One day, he said to me, “We’re going to a magic convention.” I said, “What’s a magic convention?” He says, “It’s a convention where you go and all the magicians perform, teach, and entertain,” and he said, “We’re going to go as dealers —I rented a table for you.” I said, “Ken, I don’t think I can do that.” He said: “You can do it. You’ll do fine.”

I was really very apprehensive at that point, but we packed up a couple bags of stuff and we go up to York, Pennsylvania. I go into the room where all the dealers exhibit, and I set up a table. And I’m next to two of the best demonstrators in the business. One of them was named lrv Weiner, a wonderful guy from Boston. He just died recently. To pitch, lrv would get up on a chair because he was so short, and I used to stand there and watch him with my mouth open. I couldn’t sell anything because I was so busy watching him. The guy was fantastic. He was selling like crazy. And I watched him for a couple days there and finally got my feet wet a little bit. I realized that this is what you have to do to sell magic. You have to show it.

Through the years, we’ve gone to lots of magic conventions. That’s a big thing for us. When we go to conventions, if we have a trick that we can show and fool them, they’re going to buy it. We’re slowing down now, because l’m getting old and I can’t take the push anymore. I don’t like to toot my own horn, but everywhere that I go, I probably do as well if not better than everyone there because I demonstrate.

Maybe twenty, twenty-five years ago, in going to these conventions, I found that if you offer something in return they will give you either a free dealer’s table, or free registration, or sometimes they’ll pay all your expenses. So I put together this ten-minute act —a spoof of everything that goes wrong with a magic act. l’d call myself Parnell Zorch. It wasn’t meant for the public. The kicker at the whole end of the show: I wore a toupee for about a year, but hated it, so I stopped wearing the thing. I still had it at home, though, and I was trying to figure something funny to do with it. I used to produce a little skunk, running him through my hands and so on as if he were real, and l’d have the skunk jump out of my hand. So when I leaned down to pick him up, the “toup” would fall off, and l’d pick that up and start working it like it was the skunk, you know, and the audience went hysterical. They went hysterical.

The act became so popular that I did it everywhere. I did it in Europe, I did it all over the United States, at every convention I went to. I did it about two years ago in Texas, and I got a standing ovation for it. But I retired the act and don’t do it anymore.

The greatest thrill for a magician is to fool your peers. A lot of magicians will buy a trick if it fools them. That’s not how you should really buy tricks, but everybody does.

MAGIC SHOPS USED TO BE A VERY RARE THING, but now they’re all over the place. Shopping malls. Las Vegas must have twenty shops there. I think another thing that’s hurt us is the Internet. We have a website, and the best thing that I get out of the website are people that come into the shop here who say, “Oh, I saw your website and I’m coming in to watch.” So that has been a plus. The minus end of it is, the Internet has attracted a tremendous amount of people who work out of their homes, out of their garages — no overhead. The problem is that these guys can offer the same product that we carry for maybe half the price or a third off the price. We can’t compete with that. We’ve got tremendous overhead. We’ve got to at least make our rent.

Some shops, you have to almost beg them to demonstrate. Some of them don’t even know how to demonstrate. I’ve always felt that if people buy, they want to see it. We’ve had some pretty good demonstrators over the years. We had one fellow named Thessalonia Jackson. Thess was a ghetto kid — a poor, poor ghetto kid. He came in one time and wanted to go to work for us. He was great. He was so good behind the counter. People used to just come in to watch him work. There was a fellow named John Marshall who lived in Virginia who kind of took him under his wing, and he knew he was a poor kid. John would come in and say: “Look, whatever Thess wants, give it to him. Just send me the bill. “

Thess put together a really good act, and he worked a couple conventions, and he just got a standing ovation. It was great. Now, you might say he’s still a magician. He’s now started his own church in Bronx, New York, and another church in Jamaica or one of the islands, I don’t know which one. And now he calls himself Dr. DePrince. I think he legally changed his named to DePrince. I still see him once in a while. He’s quite a guy. Do you remember the old Fourth of July snakes? The little pellet that you put a match to and it comes out like a snake? You can’t buy those anymore, but Thess used to use them to remove the spirits. Somebody would light the flame with pieces of paper, and he’d pop the pellet in there, and he’d stick it down there and burn it, and you’d see the things, you could see they were leaving — the evil spirits. What a character. Then, there was a newspaper in New York, I don’t remember the name of it — he used to run an ad in there: “Send a dollar and ask DePrince, and he will answer any question for a dollar.” He got thousands of dollars doing this. Thess is quite a guy.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2000 issue of Regardie’s Power.