Washington’s Merchant Prince

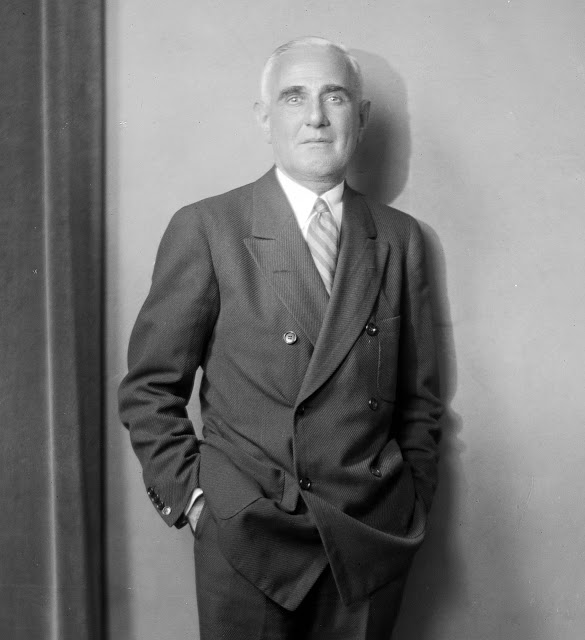

IN AN ERA OF PROSPERITY AND PEACE, OF SPORTY CARS and speakeasies, of Calvin Coolidge and Al Capone, he led a fashion-conscious city through the Roaring Twenties. His name was Julius Garfinckel, and in his time he reigned as the merchant prince of the nation’s capital.

To the wives and daughters (and mistresses as well) of Washington’s statesmen and business leaders, Garfinckel’s name was synonymous with beauty, elegance, and good taste. And from a humble start and a philosophy of quality, he infused the specialty store that bore his name with the unmistakable aura of exclusivity and respectability — and made a handsome fortune in the process.

Since the early ’70s, the fruits of his labor — now a retailing empire with the imposing name of Garfinckel, Brooks Brothers, Miller & Rhoads — have seemed ripe for outside takeover. Several conglomerates have made the attempt — most recently Allied Stores of New York — showering Garfinckel’s in a sea of attendant publicity.

Julius Garfinckel would not be amused. He prized his independence almost as much as his privacy, for he was an extraordinarily shy and retiring man, staying curiously aloof from the circles of society in which his customers traveled. He shunned publicity of any kind, leading a sheltered, shadowy life that allowed snapshots, but no lasting portrait. And much of what is known of him today often leaves more questions asked than answered.

He was a man of many eccentricities, though few knew him at close enough range to notice them. A teetotaler, he never touched a drink; a vegetarian, his simple diet consisted almost entirely of salads. When he talked face to face with taller people, he would rise up on his tiptoes, perhaps unconsciously compensating for his slight stature, balancing himself during the entire conversation. After meeting someone, he would slip away at the first opportunity to wash his hands, fearing that he might pick up germs of some kind. He liked to work outdoors on all but the coldest days, transacting business as gusting winds fanned papers on the desk he had placed on the eighth-floor balcony of his store.

Though he had belonged to one Jewish club around the turn of the century, Garfinckel was a member of the Unitarian church here by 1910. It visibly angered him when others assumed he was Jewish. And throughout its early history, the specialty store hired no Jewish employees.

And even though he reigned as Washington’s arbiter of ladies’ fashion, he remained a bachelor all his life, and was sometimes embarrassed and frightened in the company of women. Indeed, he would not see female acquaintances, customers, or employees in his office unless his secretary was present.

As one newspaper obituary reported following his death in 1936, “Mr. Garfinckel kept to himself to such a degree that only the barest outlines of his history are known, even to the handful of men who knew him most intimately. And these friends could not be said to have really been ‘close’ to Mr. Garfinckel.”

For that reason, as much as any other, Garfinckel remains one of the most enigmatic figures in local business history. A tradition more than an individual, he somehow evaded the legendary status conferred on many Washingtonians of lesser accomplishment.

The store he founded 76 years ago is now only one part of a major retailing corporation. But Garfinckel’s more personal contributions to the city of Washington have been largely forgotten, attributable to his own passion for privacy and the transient nature of the nation’s capital.

His posthumous philanthropies to Washington and its citizens — on the order of $6 million — have earned little more than a footnote in local history books.

But that is probably the way Julius Garfinckel would have preferred it.

HE WAS BORN ON NOVEMBER 5, 1874, in Syracuse, New York. the son of Harris and Hannah (Harrison) Garfinkle. (In the early 1920s, Julius Garfinkle changed his name to “Garfinckel,” the spelling used throughout this story.) Garfinckel’s parents had moved to New York from Louisiana, where the family’s ancestors had settled in the state’s early period of expansion, and soon were to return to the South. They had five children, including Julius and his twin sister Julia, but Garfinckel’s mother was widowed at an early age and raised them all on her own. By all accounts, Julius worshipped his mother, but it didn’t prevent him from leaving home at an early age.

Sometime around 1890, as so many other young men did, Julius Garfinckel headed West. “He was about 16 years old when he went to Colorado,” says William Townsend Pheiffer, Garfinckel’s nephew. “It was during the mining boom in Colorado, and he was fascinated by the idea of going into mining.” Garfinckel didn’t have enough money to finance himself while looking for a job in the mines, so he started working as a stockroom boy for the Denver Dry Goods Company. In 1893. he found work as a clerk in the J.J. Joslin Dry Goods Company (J.C. Penney got his start in retailing at the same company). Garfinckel worked at Joslin’s for five years, living at several boarding houses close to the store. In December 1889, he closed his account at the Colorado National Bank (where he had saved almost $1,700) and moved to Washington, D.C.

Soon after his arrival he got a job with Parker, Bridget & Company, a reputable Washington retailer at 9th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. During his first summer in Washington, Garfinckel traveled down to Mount Vernon for Interdependence Day, where he bought a small wooden hatchet (he used the souvenir as a paperweight for the rest of his life). In 1901, he enrolled in the Berlitz School of Languages, presumably to learn French so that he could converse with the Paris fashion houses. That same year, he was making frequent trips for Parker, Bridget & Company to New York City, staying at the Hotel Netherland for days at a time and purchasing clothing, fabrics, and accessories at Manhattan’s leading establishments.

But Garfinckel was itching to get out on his own. In 1905, he left Parker, Bridget & Company and leased the basement, first floor, and balcony of a seven-story, red brick building trimmed with brownstone at 1226 F Street, N.W. “It was just as natural as it could be, because he was a rugged individualist,” Pheiffer says. “He wasn’t going to work for anybody longer than he had to, and when he had enough money saved up, he just opened his own shop.”

The store opened its doors with little fanfare on October 2, and Garfinckel was said to have told his eight employees: “Every customer who comes in here is to be considered as a guest, and treated as such.” He had filled his new store with fine imported and American clothing and furs, and most of the store’s early customers were personal friends of the then-31-year-old Garfinckel and his employees. On opening day, Garfinckel carefully observed a time-honored business custom: he tucked a bill into a small envelope, marking it “My first five dollars.”

Trade at the small F Street location expanded quickly — in its first 10 months, the store grossed nearly $167,000. Business continued at such a rapid pace that nearly every season, Garfinckel was forced to move into yet another of the floors upstairs, which had been used by a piano company as storage space. “Whenever our business grew to the point where we needed more room,” a longtime employee recalled years later, “we moved out another floor of pianos.”

Garfinckel’s earliest motto was “Only the best goods,” reflecting his guiding philosophy of quality and good taste. That ideal was important in securing the public’s confidence in his new enterprise and, he often noted, it had no thought of gain behind it. His store had adopted the one-price policy pioneered by a competitor, Woodward & Lothrop, a practice almost revolutionary in those days. One story has it that a clerk once approached Garfinckel about allowing one customer a discount on a large purchase. The owner’s reply, in writing, became a store policy: “If your customer should purchase as much as a thousand dollars worth of goods from you and offer to pay you in cash and should then ask the question, ‘Could there be a discount?’ you are instructed to tell the customer that the one thing the personnel in Garfinckel & Co. is instructed NOT to do is to approach the head of the firm with the suggestion for discounts. This store will have but one price for every customer.”

When Garfinckel ran out of floors at 1226 F Street, he was forced to lease the corner building that had been occupied by Brentano’s book store. Henry Strong, owner of the corner property, added floors to the structure to accommodate Garfinckel’s burgeoning business. Garfinckel and his buyers continued to scout New York and Paris for the finest goods and latest fashions available, and it was the leading emporium for Washington’s elite upper sets.

WITHIN A FEW YEARS, THE GARFINCKEL STORE was doing better than $2 million in business annually. By the mid-1920s, the F Street shopping corridor had become to Washington what Fifth Avenue was to New York, and Julius Garfinckel had played a major role in its commercial development. The society editor of the Washington Times portrayed the atmosphere of the era in this way: “The F Street promenade, through successive generations of flappers, has become an institution. It is the social butterfly’s afternoon relaxation; it is the fitting touch of gaiety to the busy government worker’s Saturday half-holiday. Lovely, filmy frocks for the ballroom, smartly cut street gowns, and gloriously flashing gems to lend the perfect touch to any costume call to the eye of the feminine promenader from show windows. Beginning at 14th Street, the F-Streeters can find anything their hearts desire.”

In 1929, Garfinckel announced that he would build a new, nine-story building at the northwest corner of 14th and F streets, N.W. For more than a decade, Garfinckel had been quietly but methodically assembling the properties on which to build the new store. But at the hands of Washington’s professional planners and amateur aesthetes, his grand plans ran into a grand snag.

Garfinckel had wanted to build his new, 130-foot store on the corner, but one-year-old regulations of the city’s Zoning Commission, designed to maintain Washington’s “level” skyline, prohibited builders from erecting structures more than 110 feet tall without setbacks. (That’s why so many older Washington buildings have pyramid configurations near the top floors.) Garfinckel’s builder (Washington’s Chas. H. Thompkins) and architect (Starrett & Van Vleck of New York) argued his case before the Zoning Commission, pointing out that the National Press Building, diagonally opposite from the proposed site, rose to the full 130-foot level without setbacks. But the commission nevertheless rejected Garfinckel’s plans, and his architects went back to the drawing boards, eventually coming up with a plan that satisfied the protectors —official and self-appointed — of Washington’s skyline.

On October 6, 1930, almost 25 years to the day after he opened his first store, Garfinckel and his 350 employees, augmented by 250 new ones, moved into the new building. It included such modern features as a cold-storage vault for furs, a pneumatic-tube system for relaying orders and messages throughout the store, and an automatic sprinkler system for fire protection. But most remarkable of all, the store’s grand opening — for which Mrs. Herbert Hoover cut the ribbon — was less than a year after “Black Tuesday” on the New York Stock Exchange.

“It was a bad time when we opened up there in 1930,” recalls Wilbur Claflin, who went to work for Garfinckel in 1924. “There were a lot of stores in Washington closing up and going bankrupt, and I don’t think anybody else could have made it. But he was a shrewd businessman, and he made it.” Jennings Snider, who started in Garfinckel’s accounting department the same year, says “the contracts were made and the prices set on the contracts before the bottom fell out of the market, The new store was built after the collapse, and people were sure that he was going to go broke. But he was a very conservative man and had quite a bit of his own cash, so his loan was relatively small. His obligations were light enough that he only lost money one year, and that was a very modest amount. And, of course, it was a sole proprietorship —he had no stockholders to clamor for dividends. So it didn’t take much to carry the business. “

More than any other, Garfinckel’s new store brought the grandeur of New York and Paris to the nation’s capital, and incredibly it continued to prosper through the turbulent times of the 1930s. Its reputation stretched way beyond Washington as a favorite shopping place for first ladies, the wives of diplomats and members of Congress, and others who frequented the active social circuit Garfinckel himself avoided with a passion. President Calvin Coolidge used to walk by the original store’s big display window on his way to the White House, later calling the store to order a dress or a gown he thought would look nice on his wife. (Garfinckel, incidentally, insisted that mannequins in the store windows be headless, armless, and legless, so that nothing would detract from the clothes themselves.) In the new store, employees did their best to keep crowds away from Eleanor Roosevelt; on one occasion, the storage vault was unlocked on a holiday so that President Roosevelt could take a favorite fur-lined overcoat along on a trip.

Garfinckel had succeeded in carving out an exceedingly lucrative niche in Washington’s retail market, and much of it could be attributed to his distinctive business philosophy. He told his buyers and employees that he wanted no other store in the Washington area selling the same goods — if, in fact, he found another store duplicating Garfinckel specialties, they were discontinued at 14th and F streets. “He loved his store, and he was called the ‘Prince of Broadway’ because he would go up to New York all the time and select his clothes on Seventh Avenue,” recalls Esma Maybee, who was hired by Garfinckel himself in the early 1930s. “He was treated like a crown prince when he went up to New York, and they thought the world of him because he had such good taste in what he put in his store. He never had anything that any other buyer had within 150 miles of Washington — in other words, his clothes were all unique. One time he had me go out and do some comparative shopping for him, and when I didn’t get exactly what he wanted the first time he sent me back.”

GARFINCKEL’S NAME RARELY APPEARED IN NEWSPAPERS — outside of his store’s advertisements — but many reporters working in the National Press Building across the street came to be quite familiar with him. The store had been designed with belt courses, or terraces, running along the fourth and eighth floors, and reporters had an unobstructed view of Garfinckel’s open-air office on the upper balcony. For most of the year, they often could watch a steady stream of young women going out to model clothes for Garfinckel. “He loved the sun, and he had a little awning put over the corner,” says June Isherwood, who started her career at Garfinckel’s as a model. “He had his desk put out there from early spring into late fall, and he would conduct all of his business out there. We’d be out there on broiling hot days, and on days we considered very cold.” Garfinckel, one story goes, occasionally would be seen emerging from the elevator doors on the ground floor and racing out to the street, in search of papers blown off his outdoor desk by unexpected gusts of wind.

For more than 20 years, Garfinckel lived quietly on the seventh floor of the 380-room Burlington Hotel on Vermont Avenue at Thomas Circle. A 1924 advertisement for the hotel highlighted “music every evening” and “a table d’hote dinner, $1.00 and $1.50, on which we spare no expense.” But when the elegant Hay-Adams House was opened in 1930 by Washington real estate magnate Harry Wardman, Garfinckel moved into a spacious half-floor suite overlooking the White House and Lafayette Park. The new apartment housed his substantial and growing library, a broad collection of biographies, poetry, history, and classical and modern literature reflecting his own cultivated and catholic tastes. Garfinckel’s library eventually was to number more than 1,300 volumes, including a set of books he had acquired in Denver for $25 and brought with him to Washington: the complete works of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Garfinckel also accumulated a valuable assortment of oriental rugs and objets d’art, but his one real passion was the work of artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Over the years, he formed one of the largest private collections of Whistler drypoints and etchings, which graced the walls of his suite at the Hay-Adams.

GARFINCKEL’S SINGULAR DEDICATION TO HIS OWN BUSINESS left little room for anything else. He arrived at the store early and stayed long after most employees had left for the day, often working on Sundays and holidays as well. He was fastidious not only about his diet, but about keeping his figure lean and trim, and he was accustomed to taking long, brisk walks each morning before coming into work. “He would walk down around the Ellipse early in the morning, on rainy, bad days as well as good days,” says Jennings Snider. “I remember one occasion — this was about seven o’clock on a cloudy, winter morning — it was hardly daylight, and he admitted himself to the store on the F Street side with his key. He surprised the watchman, and the watchman pulled a gun on him. It scared the life out of him, but he had to compliment the watchman on being alert.”

Other than his early-morning walks, Garfinckel’s sole known recreation was horseback riding. He and his thoroughbred hunter were a familiar sight every Sunday morning on the bridle paths stretching the length of Rock Creek Park. Garfinckel usually rode alone, but President Coolidge was an occasional riding companion.

The strict working regimen Garfinckel prescribed for himself applied to his employees as well. “He would go through every department twice a day and speak to all the employees,” recalls June Isherwood. “He knew them all by name and he knew about their families, and they loved that. He was very stern, and yet he had a sense of humor, too. Whenever he was leaving the eighth floor, the word would go out — ‘Mr. Garfinckel is on the way down’ — so everyone was alerted.” Esma Maybee remembers Garfinckel as “a very charming person, very proud, very dignified. He had a nice stance. We all knew him, and everyone liked him, but he had very strict ideas about how to run the store and how to treat the sales people. He wanted you to wear either white or navy blue in the summer. You could wear black, but you couldn’t wear any brown . He just didn’t want to see anyone in those colors. And you had to buy your clothes at the store, which was a little expensive for the clerks.”

As the resident merchant prince of 14th and F streets, Garfinckel was monarch of all he surveyed. “He saw and personally approved of almost every item that was bought for the store,” Isherwood says. “Manufacturers would send or would bring down their trunks full of merchandise. They came to see him. I modeled everything from teenagers’ to old ladies’ dresses, because he wanted to see everything on models before he bought it or let his buyers buy it. He ruled everything, and he knew exactly what was coming into the store. That was his way of working.”

Many Washington women reveled in the personal attention lavished upon them by Julius Garfinckel, and they regarded him as the final arbiter of elegance and good taste. “So many prominent women had bought clothing from him for years, and they would hardly make a choice on a dress without having him come to look at it and see that it was proper,” Snider says. “And even in those days, imported dresses were selling for $250, $300.” And as Isherwood remembers, “It was all a very personal business with him. Mr. Garfinckel would know some woman’s daughter was going to be married, so when he went to Paris on one of his trips he would personally choose a wedding gown or a going-away costume. He liked to do things like that, and it meant a lot in those days.”

Almost every year, Garfinckel traveled to Europe — but more for business than for pleasure —staying six or seven weeks at a time. His mission was to study the latest Parisian styles and to buy fabrics and order custom-made designer clothing for his store. To this day, the legend persists that at one time Garfinckel operated a store in Paris. As early as 1911, the company’s advertisements listed New York and Paris at the top, and a 1931 Garfinckel’s letterhead contains the headings Paris, London, Vienna, and Berlin. But it’s likely these designations were only the locations of the store’s representatives — buyers and agents — included in the store’s ads to underscore Garfinckel’s reputation for imported, one-of-a-kind merchandise.

Despite his shy and retiring disposition, Garfinckel’s civic activities were wide-ranging, and he was regarded as one of Washington’s model citizens. He was a director of the Riggs National Bank, Potomac Electric Power Company, and Emergency Hospital. He was a trustee of George Washington University, Gallaudet College (his good friend and pastor, Dr. Ulysses G.B. Pierce, was secretary of the board of directors and probably invited Garfinckel to accept the position), the Columbia Institute for the Deaf, and an advisory trustee of the YWCA. He was a vice president of the D.C. chapter of the Boy Scouts of America, and in January 1936 received the Silver Beaver award for distinguished service to the Boy Scout movement. He was a 32nd degree Mason, a member of the Temple Noyes Lodge, which he entered in 1909. He was also a member of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Columbia Historical Society, and the Washington Board of Trade. He joined the Congressional Country Club, the Columbia Country Club, and the Racquet Club. During the First World War, Garfinckel served on the D.C. Draft Appeals Board.

BUT OTHER THAN HIS HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL BUSINESS, Garfinckel’s greatest interest unquestionably was in his church, All Souls’ Unitarian, at 16th and Harvard streets, N.W. He was one of its principal financial supporters, and played an active role on the finance and building committees. He achieved an outstanding reputation as an investor, advising his church and the civic groups to which he belonged on how to manage their funds for maximum return. But there was one rapidly expanding enterprise in which they could not invest — Julius Garfinckel & Company — he owned 100 percent of the company.

Though possessed of no college education, Julius Garfinckel was a self-made and largely self-educated man. He was a voracious reader of books, magazines, and newspapers, and an inveterate clipper of articles that might have some use in either his business or personal life. From out-of-town newspapers he often would clip advertisements for other specialty and department stores to see what new goods they were offering and to search for new slogans and catch-phrases. But above all, he looked for sayings of the day, adages, and bits of philosophy and humor that were printed in great volume in the newspapers of the early 1900s. (A few examples: “If God be for us, who can be against us?”, “Do not allow anything to upset you.”) Sometime in 1906, a year after he had opened his first specialty store at the corner of 13th and F streets in downtown Washington, Garfinckel was reading a newspaper obituary of Chicago department store owner Marshall Field. A brief passage outlining Field’s business philosophy caught Garfinckel’s eye, and he clipped it from the newspaper to be filed away for future reference. In pencil, he carefully marked these words about Field: “This man’s greatness lay in his perseverance, his quick appreciation of opportunity, his courage, and above all, his devotion to the sterling principle of fair dealing.”

Over the next 30 years, with nearly identical attributes, Julius Garfinckel was to become Washington’s own merchant prince. He was, as nephew William Pheiffer says, “an aristocrat to his fingertips.” But his overriding penchant for privacy was unyielding, and even today, little more is known about Garfinckel than in his heyday.

“I traveled with him on several trips to Europe, and we were very close,” says Pheiffer. “He was almost like a father to me. He was a very private person, and he had very few intimate friends. He wasn’t reclusive by any means, but he would run a country mile to keep from being regarded as a publicity-seeker. He had a fine sense of humor, and he was a very human person, but he was difficult to really get to know because he was so shy — he really was a shy man. He just shunned like the devil any effort to elicit from him any degree of self-praise. He was so modest that he wouldn’t talk about himself, wouldn’t reminisce. “

By 1936, Garfinckel’s store had topped $3 million in net sales, America was easing itself out of the Great Depression, the federal bureaucracy was growing fast with the New Deal, and everything was looking up. Though Garfinckel had suffered a fall from his horse that year riding in Rock Creek Park, breaking some ribs, he recovered enough to make a mid-summer foray to Europe with his nephew on the Queen Mary. He returned to Washington in hopes of devoting himself to the completion of plans for the opening of the store’s “mysterious seventh,” the floor that had remained dark for nearly six years (Garfinckel was planning an extravagant beauty salon there and the tea room that later opened on the fifth floor).

When he returned to Washington, he didn’t feel well. And because of his strict physical regimen he was used to good health. He went to his doctor, and then to Central Dispensary and Emergency Hospital for tests and treatment. But the diagnosis was terminal cancer. And at 8:40 p.m. on November 5, 1936, his 62nd birthday, the merchant prince died.

Though few could claim to know him well, Garfinckel’s sudden death came as a decided shock to Washingtonians. His will, filed for probate four days later, revealed to many of them for the first time a more complete picture of Julius Garfinckel. In the most exacting terms, his $6 million estate was laid out as follows:

♦ All persons employed by the store for at least nine years (there were 109) were to receive $1,000 each. Five relatives and 11 longtime Garfinckel employees were granted annuities ranging from $300 to $10,000 a year.

♦ Washington’s Central Dispensary and Emergency Hospital was granted $50,000 for its work “in connection with the relief of human suffering.”

♦ The All Souls’ Church was given $50,000 to establish and maintain a home for church members who, “by reason of advanced age or other disability, are incapacitated from earning their own living.”

♦ The Corcoran Gallery of Art was given Garfinckel’s entire collection of Whistler drypoints and etchings.

But unquestionably the biggest surprise of Garfinckel’s will regarded the disposition of the balance of his estate, later estimated at $4 million. Over the years, he saw that women were often forced to go to work unexpectedly without the benefits of education or special training, making their struggle to earn a living for their families more difficult and eroding their earning potential. Garfinckel’s sympathy for working women originated with his mother, but must have been deepened by the great numbers of women who beseeched him for jobs during the Depression.

Garfinckel directed that the bulk of his estate be used to create a trust fund for a home and school “to be known as the Hannah Harrison School of Industrial Arts, in memory of my mother, whose maiden name was Hannah Harrison.” He stipulated that the school, to be established and operated by the Washington YWCA, be devoted to “the purpose of providing worthy women, under the necessity of earning their own livelihoods, a school wherein may be taught such useful occupations as stenography, typewriter operating, bookkeeping and accountancy, dressmaking, millinery, and other lines of endeavor suitable to women.” And, Garfinckel further directed, “such women may receive, without cost and expense to them, lodging and board in surroundings that will be comfortable, healthful, and attractive.”

Following Garfinckel’s death, a group of trustees operated the store for three years, in preparation for forming a corporation and selling stock to the public. In September 1939, what was said to be the largest amount of stock — with the exception of public-utility financing — ever offered for public sale in Washington was quickly snapped up by loyal customers and investors familiar with the Garfinckel ethic and traditional profitability. [In 1964, Garfinckel’s acquired control of Brooks Brothers, whose history stretches back to 1818, and in 1950, the New York-based A. DePinna Company, which later was closed. Since that time, the expanded corporation was merged with Miller & Rhoads of Richmond and the Knoxville-based Miller’s Inc.]

Nestled in seven wooded acres of ground overlooking the Potomac River from the heights of MacArthur Boulevard is Julius Garfinckel’s most enduring legacy, today called the Hannah Harrison Career Center. The special focus of the YWCA’s career training center is the displaced homemaker: the woman over 35 who finds herself without marketable skills after years of homemaking. To keep up with the pressures of inflation, the center occasionally hosts the conferences and seminars of Washington businesses. A portrait of Garfinckel’s mother has hung in the entranceway since the school’s opening more than three decades ago, and a fresh bouquet of flowers is placed under the picture every day.

THE NIGHT BEFORE JULIUS GARFINCKEL’S FUNERAL, Ulysses Pierce had told reporters, “Three words come to my mind which most accurately sum up his character: efficiency, abstemiousness, and public spirit. His business career in Washington was nothing short of a romance, and we have lost a most esteemed brother and citizen.”

Today, at ten o’clock sharp six days a week, an important part of that romance with the city of Washington continues. Two sets of huge doors at Garfinckel’s downtown store swing open to dozens of shoppers waiting outside, many of them older women whose regular visits are as much a social occasion as a shopping excursion. The polished, uncluttered wood-and-glass counters, the ornate elevators, the absence of garish signs ballyhooing the latest sales, and the unusually wide aisles recall a more comfortable, nostalgic era of retailing in downtown Washington. It is almost an endangered urban species in these days of splashy shopping malls and sterile, warehouse-like discount houses.

And that may be just the reason why so many people patiently wait outside before opening time: it is one of the few places left where, as Julius Garfinckel wanted, customers are treated as guests, and where shoppers can seek refuge and recognition in a sea of anonymity. With the passage of 45 years, not many can be expected to remember Julius Garfinckel, and that’s probably the way he would have wanted it. For even to his departing wish — that his grave be “marked only by a simple stone, on which the only inscription shall be my name” — Julius Garfinckel sought, and was granted, a kind of anonymity of his own.

This article originally appeared in the September/October 1981 issue of Regardie’s.